Timeline of Spirit

Spirit is a robotic rover that was active on the planet Mars from 2004 to 2010. Launched on June 10, 2003, Spirit landed on Mars' Meridiani Planum on January 4, 2004, three weeks after its twin Opportunity (MER-B), also part of NASA's Mars Exploration Rover Mission, touched down on the other side of the planet. Spirit became immobile in 2009 and ceased communications in 2010. NASA ended efforts to free the rover and eventually ended the mission on May 25, 2011.[1]

2004[edit]

The Spirit Mars rover landed successfully on the surface of Mars on 04:35 Spacecraft Event Time (SCET) on January 4, 2004. This was the start of its 90-sol mission, but solar cell cleaning events would mean it was the start of a much longer mission, lasting until 2010.

Landing site: Columbia Memorial Station[edit]

Spirit was targeted to a site that appears to have been affected by liquid water in the past, the crater Gusev, a possible former lake in a giant impact crater about 10 km (6.2 mi) from the center of the target ellipse[2] at 14°34′18″S 175°28′43″E / 14.5718°S 175.4785°E.[3]

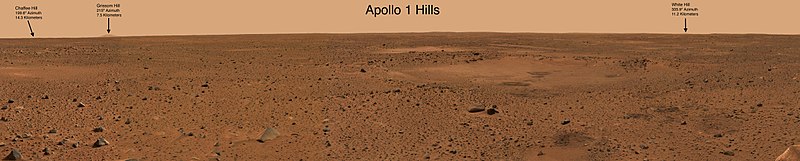

After the airbag-protected landing craft settled onto the surface, the rover rolled out to take panoramic images. These give scientists the information they need to select promising geological targets and drive to those locations to perform on-site scientific investigations. The panoramic image below shows a slightly rolling surface, littered with small rocks, with hills on the horizon up to 3 kilometers (1.9 mi) away.[4] The MER team named the landing site "Columbia Memorial Station," in honor of the seven astronauts killed in the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster.

"Sleepy Hollow," a shallow depression in the Mars ground at the right side of the above picture, was targeted as an early destination when the rover drove off its lander platform. NASA scientists were very interested in this crater. It is 9 meters (30 ft) across and about 12 meters (39 ft) north of the lander.

First color image[edit]

To the right is the first color image derived from images taken by the panoramic camera on the Mars Exploration Rover Spirit. It was the highest resolution image taken on the surface of another planet. According to the camera designer Jim Bell of Cornell University, the panoramic mosaic consists of four pancam images high by three wide. The picture shown originally had a full size of 4,000 by 3,000 pixels. However, a complete pancam panorama is even 8 times larger than that, and could be taken in stereo (i.e., two complete pictures, making the resolution twice as large again.) The colors are fairly accurate. (For a technical explanation, see colors outside the range of the human eye.)

The MER pancams are black-and-white instruments. Thirteen rotating filter wheels produce multiple images of the same scene at different wavelengths. Once received on Earth, these images can be combined to produce color images.[5]

Sol 17 flash memory management anomaly[edit]

On January 21, 2004 (sol 17), Spirit abruptly ceased communicating with mission control. The next day the rover radioed a 7.8 bit/s beep, confirming that it had received a transmission from Earth but indicating that the craft believed it was in a fault mode. Commands would only be responded to intermittently. This was described as a very serious anomaly, but potentially recoverable if it were a software or memory corruption issue rather than a serious hardware failure. Spirit was commanded to transmit engineering data, and on January 23 sent several short low-bitrate messages before finally transmitting 73 megabits via X band to Mars Odyssey. The readings from the engineering data suggested that the rover was not staying in sleep mode. As such, it was wasting its battery energy and overheating – risk factors that could potentially destroy the rover if not fixed soon. On sol 20, the command team sent it the command SHUTDWN_DMT_TIL ("Shutdown Dammit Until") to try to cause it to suspend itself until a given time. It seemingly ignored the command.

The leading theory at the time was that the rover was stuck in a "reboot loop". The rover was programmed to reboot if there was a fault aboard. However, if there was a fault that occurred during reboot, it would continue to reboot forever. The fact that the problem persisted through reboot suggested that the error was not in RAM, but in either the flash memory, the EEPROM, or a hardware fault. The last case would likely doom the rover. Anticipating the potential for errors in the flash memory and EEPROM, the designers had made it so that the rover could be booted without ever touching the flash memory. The radio itself could decode a limited command set – enough to tell the rover to reboot without using flash. Without access to flash memory the reboot cycle was broken.

On January 24, 2004 (sol 19) the rover repair team announced that the problem was with Spirit's flash memory and the software that wrote to it. The flash hardware was believed to be working correctly but the file management module in the software was "not robust enough" for the operations the Spirit was engaged in when the problem occurred, indicating that the problem was caused by a software bug as opposed to faulty hardware. NASA engineers finally came to the conclusion that there were too many files on the file system, which was a relatively minor problem. Most of these files contained unneeded in-flight data. After realizing what the problem was, the engineers deleted some files, and eventually reformatted the entire flash memory system. On February 6 (sol 32), the rover was restored to its original working condition, and science activities resumed.[6]

First intentional grinding of a rock on Mars[edit]

For the first intentional grinding of a rock on Mars, the Spirit team chose a rock called "Adirondack". To make the drive there, the rover turned 40 degrees in short arcs totaling 95 centimetres (37 in). It then turned in place to face the target rock and drove four short moves straightforward totaling 1.9 m (6 ft 3 in). Adirondack was chosen over another rock called "Sashimi", which was closer to the rover, as Adirondack's surface was smoother, making it more suitable for the Rock Abrasion Tool (aka "RAT").[7]

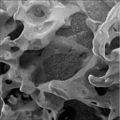

Spirit made a small depression in the rock, 45.5 millimetres (1.79 in) in diameter and 2.65 millimetres (0.104 in) deep. Examination of the freshly exposed interior with the rover's microscopic imager and other instruments confirmed that the rock is volcanic basalt.[8]

Humphrey rock[edit]

On March 5, 2004, NASA announced that Spirit had found hints of water history on Mars in a rock dubbed "Humphrey". Raymond Arvidson, the McDonnell University Professor and chair of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, reported during a NASA press conference: "If we found this rock on Earth, we would say it is a volcanic rock that had a little fluid moving through it." In contrast to the rocks found by the twin rover Opportunity, this one was formed from magma and then acquired bright material in small crevices, which look like crystallized minerals. If this interpretation holds true, the minerals were most likely dissolved in water, which was either carried inside the rock or interacted with it at a later stage, after it formed.[9]

Bonneville crater[edit]

On sol 66 March 11, 2004, Spirit reached Bonneville crater after a 400-yard (370 m) journey.[10] This crater is about 200 meters (220 yd) across with a floor about 10 meters (11 yd) below the surface.[11] JPL decided that it would be a bad idea to send the rover down into the crater, as they saw no targets of interest inside. Spirit drove along the southern rim and continued to the southwest towards the Columbia Hills.

Spirit reached Missoula crater on sol 105. The crater is roughly 100 yards (91 m) across and 20 yards (18 m) deep. Missoula crater was not considered a high priority target due to the older rocks it contained. The rover skirted the northern rim, and continued to the southeast. It then reached Lahontan crater on sol 118, and drove along the rim until sol 120. Lahontan is about 60 yards (55 m) across and about 10 yards (9.1 m) deep. A long, snaking sand dune stretches away from its southwestern side, and Spirit went around it, because loose sand dunes present an unknown risk to the ability of the rover wheels to get traction.

Columbia Hills[edit]

Spirit drove from Bonneville crater in a direct line to the Columbia Hills. The route was only directly controlled by the engineers when the terrain was difficult to navigate; otherwise, the rover drove in an autonomous mode. On sol 159, Spirit reached the first of many targets at the base of the Columbia Hills called West Spur. Hank's Hollow was studied for 23 sols. Within Hank's Hollow was the strange-looking rock dubbed "Pot of Gold". Analysing this rock was difficult for Spirit, because it lay in a slippery area. After a detailed analysis with the AXPS-and the Mößbauer instrument it was detected that it contains hematite.[12] This kind of rock can be built in connection with water.

As the produced energy from the solar panels was lowering due to the setting Sun and dust the Deep Sleep Mode was introduced. In this mode the rover was shut down completely during the night in order to save energy, even if the instruments would fail.[13] The route was selected so that the rover's panels were tilted as much as possible towards the winter sunlight.

From here, Spirit took a northerly path along the base of the hill towards the target Wooly Patch, which was studied from sol 192 to sol 199. By sol 203, Spirit had driven southward up the hill and arrived at the rock dubbed "Clovis". Clovis was ground and analyzed from sol 210 to sol 225. Following Clovis came the targets of Ebenezer (Sols 226–235), Tetl (sol 270), Uchben and Palinque (Sols 281–295), and Lutefisk (Sols 296–303). From Sols 239 to 262, Spirit powered down for solar conjunction, when communications with the Earth are blocked. Slowly, Spirit made its way around the summit of Husband Hill, and at sol 344 was ready to climb over the newly designated "Cumberland Ridge" and into "Larry's Lookout" and "Tennessee Valley". Spirit also did some communication tests with the ESA orbiter Mars Express though most of the communication was usually done with the NASA orbiters Mars Odyssey and Mars Global Surveyor.

2005[edit]

Driving up to Husband Hill[edit]

Spirit had now been on Mars for one Earth year and was driving slowly uphill towards the top of Husband Hill. This was difficult because there were many rocky obstacles and sandy parts. This led frequently to slippage and the route could not be driven as planned. In February, Spirit's computer received a software update in order to drive more autonomously.[14] On sol 371, Spirit arrived at a rock named "Peace" near the top of Cumberland Ridge. Spirit ground Peace with the RAT on sol 373. By sol 390 (mid-February 2005), Spirit was advancing towards "Larry's Lookout", by driving up the hill in reverse. The scientists at this time were trying to conserve as much energy as possible for the climb.

Spirit also investigated some targets along the way, including the soil target, "Paso Robles", which contained the highest amount of salt found on the red planet. The soil also contained a high amount of phosphorus in its composition, however not nearly as high as another rock sampled by Spirit, "Wishstone". One of the scientists working with Spirit, Dr. Steve Squyres, said of the discovery, "We're still trying to work out what this means, but clearly, with this much salt around, water had a hand here".[15]

-

Spirit's traverse up Husband Hill

-

Martian sunset by Spirit at Gusev crater, May 19, 2005.

Dust devils[edit]

On March 9, 2005 (probably during the Martian night), the rover's solar panel efficiency jumped from the original ~60% to 93%, followed on March 10, by the sighting of dust devils. NASA scientists speculated a dust devil must have swept the solar panels clean, possibly significantly extending the duration of the mission. This also marked the first time dust devils had been spotted by Spirit or Opportunity. Dust devils had previously only been photographed by the Pathfinder probe.

Mission members monitoring Spirit on Mars reported on March 12, 2005 (sol 421), that a lucky encounter with a dust devil had cleaned the robot's solar panels. Energy levels dramatically increased and daily science work was anticipated to be expanded.[16]

Husband Hill summit[edit]

As of August Spirit was only 100 metres (330 ft) away from the top. Here it was found that Husband Hill has two summits, with one a little higher than the other. On August 21 (sol 582),[17] Spirit reached the real summit of Husband Hill. The rover was the first spacecraft to climb atop a mountain on another planet. The whole distance driven totaled 4971 meters. The summit itself was flat. Spirit took a 360 degree panorama in real color, which included the whole Gusev crater. At night the rover observed the moons Phobos and Deimos in order to determine their orbits better.[18] On sol 656 Spirit surveyed the Mars sky and the opacity of the atmosphere with its pancam to make a coordinated science campaign with the Hubble Space Telescope in Earth orbit.[19]

From the peak Spirit spotted a striking formation, which was dubbed "Home Plate". This was an interesting target, but Spirit would be driven later to the McCool Hill to tilt its solar panels towards the Sun in the coming winter. At the end of October the rover was driven downhill and to Home Plate. On the way down Spirit reached the rock formation named "Comanche" on sol 690. Scientists used data from all three spectrometers to find out that about one-fourth of the composition of Comanche is magnesium iron carbonate. That concentration is 10 times higher than for any previously identified carbonate in a Martian rock. Carbonates originate in wet, near-neutral conditions but dissolve in acid. The find at Comanche is the first unambiguous evidence from the Mars Exploration Mission rovers for a past Martian environment that may have been more favorable to life than the wet but acidic conditions indicated by the rovers' earlier finds.[20]

2006[edit]

Driving to McCool Hill[edit]

In 2006 Spirit drove towards an area dubbed Home Plate, and reached it in February. For events in 2006 by NASA see NASA Spirit Archive 2006

Spirit's next stop was originally planned to be the north face of McCool Hill, where Spirit would receive adequate sunlight during the Martian winter. On March 16, 2006, JPL announced that Spirit's troublesome front wheel had stopped working altogether. Despite this, Spirit was still making progress toward McCool Hill because the control team programmed the rover to drive toward McCool Hill backwards, dragging its broken wheel.[21] In late March, Spirit encountered loose soil that was impeding its progress toward McCool Hill. A decision was made to terminate attempts to reach McCool Hill and instead park on a nearby ridge named Low Ridge Haven.

Spirit arrived at the north west corner of Home Plate, a raised and layered outcrop on sol 744 (February 2006) after an effort to maximize driving. Scientific observations were conducted with Spirit's robotic arm.

Low Ridge Haven[edit]

Reaching the ridge on April 9, 2006, and parking on the ridge with an 11° incline to the north, Spirit spent the next eight months on the ridge, spending that time undertaking observations of changes in the surrounding area.[22] No drives were attempted because of the low energy levels the rover was experiencing during the Martian winter. The rover made its first drive, a short turn to position targets of interest within reach of the robotic arm, in early November 2006, following the shortest days of winter and solar conjunction when communications with Earth were severely limited.

While at Low Ridge, Spirit imaged two rocks of similar chemical nature to that of Opportunity's Heat Shield Rock, a meteorite on the surface of Mars. Named "Zhong Shan" for Sun Yat-sen and "Allan Hills" for the location in Antarctica where several Martian meteorites have been found, they stood out against the background rocks that were darker. Further spectrographic testing is being done to determine the exact composition of these rocks, which may turn out to also be meteorites.

2007[edit]

Software upgrade[edit]

On January 4, 2007 (sol 1067), both rovers received new flight software to the onboard computers. The update was received just in time for the third anniversary of their landing. The new systems let the rovers decide whether or not to transmit an image, and whether or not to extend their arms to examine rocks, which would save much time for scientists as they would not have to sift through hundreds of images to find the one they want, or examine the surroundings to decide to extend the arms and examine the rocks.[23]

Silica Valley[edit]

Spirit's dead wheel turned out to have a silver lining. As it was traveling in March 2007, pulling the dead wheel behind, the wheel scraped off the upper layer of the Martian soil, uncovering a patch of ground that scientists say shows evidence of a past environment that would have been perfect for microbial life. It is similar to areas on Earth where water or steam from hot springs came into contact with volcanic rocks. On Earth, these are locations that tend to teem with bacteria, said rover chief scientist Steve Squyres. "We're really excited about this," he told a meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU). The area is extremely rich in silica–the main ingredient of window glass. The researchers have now concluded that the bright material must have been produced in one of two ways. One: hot-spring deposits produced when water dissolved silica at one location and then carried it to another (i.e. a geyser). Two: acidic steam rising through cracks in rocks stripped them of their mineral components, leaving silica behind. "The important thing is that whether it is one hypothesis or the other, the implications for the former habitability of Mars are pretty much the same," Squyres explained to BBC News. Hot water provides an environment in which microbes can thrive and the precipitation of that silica entombs and preserves them. Squyres added, "You can go to hot springs and you can go to fumaroles and at either place on Earth it is teeming with life – microbial life."[24][25]

Global dust storm and Home Plate[edit]

During 2007, Spirit spent several months near the base of the Home Plate plateau. On sol 1306 Spirit climbed onto the eastern edge of the plateau. In September and October it examined rocks and soils at several locations on the southern half of the plateau. On November 6, Spirit had reached the western edge of Home Plate, and started taking pictures for a panoramic overview of the western valley, with Grissom Hill and Husband Hill visible. The panorama image was published on NASA's website on January 3, 2008, to little attention, until January 23, when an independent website published a magnified detail of the image that showed a rock feature a few centimeters high resembling a humanoid figure seen from the side with its right arm partially raised.[26][27]

Towards the end of June 2007, a series of dust storms began clouding the Martian atmosphere with dust. The storms intensified and by July 20, both Spirit and Opportunity were facing the real possibility of system failure due to lack of energy. NASA released a statement to the press that said (in part) "We're rooting for our rovers to survive these storms, but they were never designed for conditions this intense".[28] The key problem caused by the dust storms was a dramatic reduction in solar energy caused by there being so much dust in the atmosphere that it was blocking 99 percent of direct sunlight to Opportunity, and slightly more to Spirit.

Normally the solar arrays on the rovers are able to generate up to 700 watt-hours (2,500 kJ) of energy per Martian day. After the storms, the amount of energy generated was greatly reduced to 128 watt-hours (460 kJ). If the rovers generate less than 150 watt-hours (540 kJ) per day they must start draining their batteries to run survival heaters. If the batteries run dry, key electrical elements are likely to fail due to the intense cold. Both rovers were put into the lowest-power setting in order to wait out the storms. In early August the storms began to clear slightly, allowing the rovers to successfully charge their batteries. They were kept in hibernation in order to wait out the remainder of the storm.[29]

2008[edit]

Hibernating[edit]

The main concern was the energy level for Spirit. To increase the amount of light hitting the solar panels, the rover was parked in the northern part of Home Plate on as steep a slope as possible. It was expected that the level of dust cover on the solar panels would increase by 70 percent and that a slope of 30 degrees would be necessary to survive the winter. In February, a tilt of 29.9 degrees was achieved. Extra energy was available at times, and a high definition panorama named Bonestell was produced. At other times when there was only enough solar energy to recharge the batteries, communication with Earth was minimized and all unnecessary instruments were switched off. At winter solstice the energy production declined to 235 watt hours per sol.[30]

Winter dust storm[edit]

On November 10, 2008, a large dust storm further reduced the output of the solar panels to 89 watt-hours (320 kJ) per day—a critically low level.[31] NASA officials were hopeful that Spirit would survive the storm, and that the energy level would rise once the storm had passed and the skies started clearing. They attempted to conserve energy by shutting down systems for extended periods of time, including the heaters. On November 13, 2008, the rover awoke and communicated with mission control as scheduled.[32]

From November 14, 2008, to November 20, 2008 (sols 1728 to 1734), Spirit averaged 169 watt-hours (610 kJ) per day. The heaters for the thermal emission spectrometer, which used about 27 watt-hours (97 kJ) per day, were disabled on November 11, 2008. Tests on the thermal emission spectrometer indicate that it was undamaged, and the heaters would be enabled with sufficient energy.[33] The solar conjunction, where the Sun is between Earth and Mars, started on November 29, 2008, and communication with the rovers was not possible until December 13, 2008.[34]

2009[edit]

Increased energy[edit]

On February 6, 2009, a beneficial wind blew off some of the dust accumulated on the panels. This led to an increase in energy output to 240 watt-hours (860 kJ) per day. NASA officials stated that this increase in energy was to be used predominantly for driving.[35]

On April 18, 2009 (sol 1879) and April 28, 2009 (sol 1889) energy output of the solar arrays were increased by cleaning events.[36][37] The energy output of Spirit's solar arrays climbed from 223 watt-hours (800 kJ) per day on March 31, 2009, to 372 watt-hours (1,340 kJ) per day on April 29, 2009.[37]

Sand trap[edit]

On May 1, 2009 (sol 1892), the rover became stuck in soft sand, the machine resting upon a cache of iron(III) sulfate (jarosite) hidden under a veneer of normal-looking soil. Iron sulfate has very little cohesion, making it difficult for the rover's wheels to gain traction.[38][39]

JPL team members simulated the situation by means of a rover mock-up and computer models in an attempt to get the rover back on track. To reproduce the same soil mechanical conditions on Earth as those prevailing on Mars under low gravity and under very weak atmospheric pressure, tests with a lighter version of a mock-up of Spirit were conducted at JPL in a special sandbox to attempt to simulate the cohesion behavior of poorly consolidated soils under low gravity.[40][41] Preliminary extrication drives began on November 17, 2009.[42]

On December 17, 2009 (sol 2116), the right-front wheel suddenly began to operate normally for the first three out of four rotations attempts. It was unknown what effect it would have on freeing the rover if the wheel became fully operational again. The right rear wheel had also stalled on November 28 (sol 2097) and remained inoperable for the remainder of the mission. This left the rover with only four fully operational wheels.[43] If the team could not gain movement and adjust the tilt of the solar panels, or gain a beneficial wind to clean the panels, the rover would only be able to sustain operations until May 2010.[44]

2010[edit]

Mars winter at Troy[edit]

On January 26, 2010 (sol 2155), after several months attempting to free the rover, NASA decided to redefine the mobile robot mission by calling it a stationary research platform. Efforts were directed in preparing a more suitable orientation of the platform in relation to the Sun in an attempt to allow a more efficient recharge of the platform's batteries. This was needed to keep some systems operational during the Martian winter.[45] On March 30, 2010, Spirit skipped a planned communication session and as anticipated from recent power-supply projections, had probably entered a low-power hibernation mode.[46]

The last communication with the rover was March 22, 2010 (sol 2208)[47] and there is a strong possibility the rover's batteries lost so much energy at some point that the mission clock stopped. In previous winters the rover was able to park on a Sun-facing slope and keep its internal temperature above −40 °C (−40 °F), but since the rover was stuck on flat ground it is estimated that its internal temperature dropped to −55 °C (−67 °F). If Spirit had survived these conditions and there had been a cleaning event, there was a possibility that with the southern summer solstice in March 2011, solar energy would increase to a level that would wake up the rover.[48]

Communication attempts[edit]

Spirit remains silent at its location, called "Troy," on the west side of Home Plate. There was no communication with the rover after March 22, 2010 (sol 2208).[49]

It is likely that Spirit experienced a low-power fault and had turned off all sub-systems, including communication, and gone into a deep sleep, trying to recharge its batteries. It is also possible that the rover had experienced a mission clock fault. If that had happened, the rover would have lost track of time and tried to remain asleep until enough sunlight struck the solar arrays to wake it. This state is called "Solar Groovy." If the rover woke up from a mission clock fault, it would only listen. Starting on July 26, 2010 (sol 2331), a new procedure to address the possible mission clock fault was implemented.

Each sol, the Deep Space Network mission controllers sent a set of X-band "Sweep & Beep" commands. If the rover had experienced a mission clock fault and then had been awoken during the day, it would have listened during brief, 20-minute intervals during each hour awake. Due to the possible clock fault, the timing of these 20-minute listening intervals was not known, so multiple "Sweep & Beep" commands were sent. If the rover heard one of these commands, it would have responded with an X-band beep signal, updating the mission controllers on its status and allowing them to investigate the state of the rover further. But even with this new strategy, there was no response from the rover.

The rover had driven 7,730.50 metres (4.80351 mi) until it became immobile.[50]

2011[edit]

Mission end[edit]

JPL continued attempts to regain contact with Spirit until May 25, 2011, when NASA announced the end of contact efforts and the completion of the mission.[51][52][53] According to NASA, the rover likely experienced excessively cold "internal temperatures" due to "inadequate energy to run its survival heaters" that, in turn, was a result of "a stressful Martian winter without much sunlight." Many critical components and connections would have been "susceptible to damage from the cold."[52] Assets that had been needed to support Spirit were transitioned to support Spirit's then still-active Opportunity rover,[51] and Mars rover Curiosity which is exploring Gale Crater and has been doing so for more than six years.[54]

Gallery[edit]

The rover could take pictures with its different cameras, but only the PanCam camera had the ability to photograph a scene with different color filters. The panorama views were usually built up from PanCam images. Spirit transferred 128,224 pictures in its lifetime.[55]

Views[edit]

-

Looking back from Bonneville crater to the landing site

-

False color image of "Mimi".

Panoramas[edit]

Microscopic images[edit]

-

Close-up of the rock Mazatzal, which was ground with the Rock Abrasion Tool on sol 82

-

Erosive effect of winds on hardened lava.

From orbit[edit]

-

Rover tracks up to sol 85 from Mars Global Surveyor

-

Spirit on September 29, 2006, beside Home Plate [56]

Maps[edit]

from January 2004 landing thru to April 2008.

(see image above, at #Mars winter at Troy, for remaining movement)

Legend: Active (white lined, ※) • Inactive • Planned (dash lined, ⁂)

References[edit]

- ^ Nelson, Jon. "Mars Exploration Rover - Spirit". NASA. Retrieved April 16, 2023.

- ^ "Gusev Crater: LandingSites". marsoweb.nas.nasa.gov.

- ^ Spaceflightnow.com, Destination Mars, Rover headed toward hilly vista for martian exploration

- ^ "APOD: 2004 January 14 – A Mars Panorama from the Spirit Rover". antwrp.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "MER color imagery, methods". Archived from the original on April 24, 2005.

- ^ Planetary Blog.

- ^ Webster, Guy (January 19, 2004). "Spirit Drives to a Rock Called 'Adirondack' for Close Inspection" (Press release). NASA. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- ^ Webster, Guy (February 9, 2004). "Mars Rover Pictures Raise 'Blueberry Muffin' Questions" (Press release). NASA. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- ^ mars.nasa.gov. "Mars Exploration Rover". marsrovers.jpl.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Spirit Updates: 2004". mars.nasa.gov. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- ^ Golombek; et al. Surfical geology of the Spirit rover traverse in Gusev Crater: dry and desiccating since the Hesperian (PDF). Second Conference on Early Mars (2004). p. 1. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

The rim is ~3 meters (9.8 ft) high and although the crater is shallow (~10 meters (33 ft) deep)

- ^ "Mars Rovers Surprises Continue". JPL website. Archived from the original on December 4, 2013. Retrieved October 6, 2006.

- ^ "Mars Exploration Rover Mission: All Spirit Updates". marsrovers.jpl.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on June 25, 2007. Retrieved November 21, 2013.

- ^ "Mars Exploration Rover Mission: All Spirit Updates". marsrovers.jpl.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on November 23, 2013. Retrieved November 21, 2013.

- ^ mars.nasa.gov; NASA, JPL. "Mars Exploration Rover". mars.nasa.gov. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- ^ David, Leonard (March 12, 2005). "Spirit Gets A Dust Devil Once-Over". Space.com. Retrieved December 1, 2006.

- ^ "Rover Update: 2005: All". mars.nasa.gov. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- ^ "NASA Rover Finds Clue to Mars' Past And Environment for Life". NASA. June 3, 2010. Retrieved May 25, 2011.

- ^ "Mars Exploration Rover Mission: All Spirit Updates". marsrovers.jpl.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on November 23, 2013. Retrieved November 21, 2013.

- ^ "NASA – Carbonate-Containing Martian Rocks (False Color)". www.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Mars Exploration Rover Mission: All Spirit Updates". marsrovers.jpl.nasa.gov.

- ^ "NASA – NASA Mars Rovers Head for New Sites After Studying Layers". www.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Old rovers learn new tricks". CBC News. January 4, 2007.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (December 11, 2007). "Mars robot unearths microbe clue". NASA says its robot rover Spirit has made one of its most significant discoveries on the surface of Mars. BBC News. Retrieved December 12, 2007.

- ^ Bertster, Guy (December 10, 2007). "Mars Rover Investigates Signs of Steamy Martian Past". Press Release. Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California. Retrieved December 12, 2007.

- ^ Planetary.org Archived April 20, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Emily Lakdawalla, Teeny little Bigfoot on Mars, January 23, 2008 | 12:41 PST | 20:41 UTC

- ^ Nemiroff, R.; Bonnell, J., eds. (January 29, 2008). "Spirit's West Valley Panorama image". Astronomy Picture of the Day. NASA.

- ^ "NASA Mars Rovers Braving Severe Dust Storms" (Press release). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. July 27, 2007. Archived from the original on January 17, 2012. Retrieved August 21, 2009.

- ^ "Martian Skies Brighten Slightly" (Press release). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. August 7, 2007. Retrieved August 21, 2009.

- ^ "Mars Exploration Rover Mission: All Spirit Updates". marsrovers.jpl.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Dust Storm Cuts Energy Supply of NASA Mars Rover Spirit" (Press release). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. November 10, 2008. Archived from the original on September 27, 2012. Retrieved August 21, 2009.

- ^ Courtland, Rachel (November 14, 2009). "Spirit rover recuperating after dust storm". New Scientist. Retrieved August 21, 2009.

- ^ "sol 1730–1736, November 14–20, 2008: Serious but Stable" (Press release). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. November 20, 2008. Retrieved August 21, 2009.

- ^ "sol 1709–1715, November 13–19, 2008: Opportunity Prepares for Two Weeks of Independent Study" (Press release). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. November 19, 2008. Retrieved August 21, 2009.

- ^ "Spirit Gets Energy Boost from Cleaner Solar Panels". NASA/JPL. Retrieved February 17, 2009.

- ^ "Another Reset and a Cleaning Event". NASA/JPL. April 22, 2009. Retrieved April 25, 2009.

- ^ a b "Well Behaved, Less Dusty, in Difficult Terrain". NASA/JPL. April 29, 2009. Retrieved May 4, 2009.

- ^ Maggie McKee (May 12, 2009). "Mars rover may not escape sand trap for weeks". New Scientist.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (May 19, 2009). "Mars rover's 5 working wheels are stuck in hidden soft spot". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 19, 2009.

- ^ "Free Spirit - jpl.nasa.gov". www.jpl.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on May 22, 2022. Retrieved February 18, 2019.

- ^ "A How a Sandbox Could Save Mars Rover". sphere.com. December 10, 2009. Archived from the original on January 17, 2010.

- ^ "Spirit Update Archive". NASA/JPL. Retrieved May 4, 2009.

- ^ "Right-Front Wheel Rotations". NASA. December 17, 2009. Archived from the original on March 18, 2012. Retrieved December 25, 2009.

- ^ "NASA's Mars Rover has Uncertain Future as Sixth Anniversary Nears". NASA. December 31, 2009. Archived from the original on March 18, 2012. Retrieved January 1, 2010.

- ^ "Now A Stationary Research Platform, NASA's Mars Rover Spirit Starts a New Chapter in Red Planet Scientific Studies". NASA. January 26, 2010. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved June 26, 2009.

- ^ "Spirit May Have Begun Months-Long Hibernation". NASA. March 31, 2010.

- ^ "Spirit status". NASA. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

- ^ A.J.S. Rayl Spirit Sleeps Soundlessly, Opportunity Turns a Corner Archived April 1, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Planetary Society July 31, 2010

- ^ Reisert, Sarah (2017). "Life on Mars". Distillations. 3 (1): 42–45. Archived from the original on March 25, 2019. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- ^ "Mars Exploration Rover Mission: All Spirit Updates". marsrovers.jpl.nasa.gov.

- ^ a b Webster, Guy (May 25, 2011). "NASA's Spirit Rover Completes Mission on Mars". NASA. Retrieved October 12, 2011.

- ^ a b "NASA Concludes Attempts to Contact Mars Rover Spirit". NASA. Archived from the original on October 11, 2011. Retrieved May 25, 2011.

- ^ Atkinson, Nancy (May 25, 2011). "End of the Road for Spirit Rover". Universe Today. Retrieved May 25, 2011.

- ^ mars.nasa.gov. "NASA's Opportunity Rover Mission on Mars Comes to End". NASA’s Mars Exploration Program. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- ^ mars.nasa.gov. "Mars Exploration Rover". marsrovers.jpl.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Catalog Page for PIA01879". photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov.

![Spirit on September 29, 2006, beside Home Plate [56]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/56/Spirit_MRO.jpg/120px-Spirit_MRO.jpg)