The Lives of Remarkable People

| Country | Soviet Union |

|---|---|

| Language | Russian |

| Genre | Biography |

| Publisher | Molodaya Gvardiya |

Publication date | Since 1933 |

The Lives of Remarkable People (Жизнь замечательных людей or acronym form of the title ЖЗЛ[1][2] or common name "жэзээлка")[3][4] is a series of fiction and biographical books intended for a mass audience. It was first published in 1890–1924 by the publishing house of F. F. Pavlenkov under the same title (two hundred biographies were published in all, after 1900 only reprints were published). Since then there have been several attempts to revive the series, but only Maxim Gorky succeeded. In 1933–1938 the series was reissued by the Association of Periodicals and Newspapers, with the numbering starting from one. After 1938, the series was published by "Molodaya Gvardiya" with a continuous numbering of issues; since 2001, the numbering has been doubled (taking into account Pavlenkov's issues). By 2010, the total number of editions exceeded one and a half thousand, and the total circulation of the series exceeded one hundred million copies.[5]

Pavlenkov's serie was accessible to public and intended to "acquaint readers with outstanding personalities of past epochs". The genre format of the series was determined by the educational goals: a popular biographical essay, focused on the great achievements of a person who left his mark on the history of world civilization. The biographies were written by famous publicists and journalists of their time (E. A. Solovyov, A. Skabichevsky). Some essays were written by professional philosophers and writers (V.S. Solovyov, N.M. Minsky). Maxim Gorky created a new format of biographies, whose heroes were world-famous figures of science and art, as well as revolutionaries. In the publishing house "Molodaya Gvardiya" a public editorial board of the series was created, which included academicians V. L. Komarov, E. M. Minsky. L. Komarov, E. V. Tarle, A. E. Fersman, professors Y. N. Tynyanov and P. F. Yudin, writers A. A. Fadeev and A.N. Tolstoy.

In the 1950s, the editors of the series formulated three main principles for selecting the texts to be published, which have been followed ever since: scientific accuracy, high literary level, and entertainment. For the author, publication in the series was a sign of recognition of his or her high social and professional status. In different years the "Molodaya Gvardiya" invited Lev Gumilevsky, Sergei Durylin, Konstantin Paustovsky, Marietta Shaginian, Kornei Chukovsky, Juri Lotman, Alexei Losev, Nathan Eidelman and many others to write biographies. Many authors of biographies, in turn, became the heroes of new books in the serie. At the same time, the tone of the texts published in the 1960s and 1970s was subordinated to the requirements of ideology, and the concept of "remarkable" was interpreted as "flawless". Most of the people chosen were ideologically upright and morally irreproachable, and very little was said about the difficulties of their destinies.

After the Dissolution of the Soviet Union, the number of copies of the series decreased significantly. This was due to competition from the media and then the Internet. The number of published books didn't increase for many years. The genre of the "classical" biography was limited to the scientific framework, the tradition of the novel biography died out, professional historians and philologists began to predominate among the authors of the series. At the same time, since the 1990s the thematic range of the series has expanded enormously: biographies of tsars, Orthodox saints, emigrant writers, figures of the White movement, Soviet and foreign film actors have been published. The flow of translated literature increased significantly.

Florentiy Pavlenkov's library of biographies and attempts of its continuation[edit]

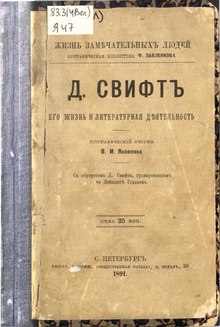

In 1890–1900 the publishing house of Florentiy Pavlenkov published a biographical library "The Lives of Remarkable People". The title was a copy of the French Vie des Hommes illustres, as well as the title of the translation of Plutarch's "Parallel Lives", which Pavlenkov greatly appreciated in his youth.[6] After the publisher's death, his executors completed the series of 200 biographies, which were reprinted until 1924. The library of biographies proved to be very popular and survived at least 40 reprints with a total circulation of 1.5 million copies (one edition was printed in 8 to 10 thousand copies). Pavlenkov's biographies were short in length, more like a popular scientific sketch stories, and cost about 25 kopecks (they were available to gymnasium and university students), characterized by high quality of the text, sometimes not devoid of artistry, and concise content. Among their authors were Vladimir Solovyov and Alexander Skabichevsky, as well as the poet Nikolai Minsky; many of the biographies are considered models of the genre. The bibliographer Nikolai Rubakin, who was one of the publishing house's heirs, highly praised the quality and importance of Pavlenkov's biographical library. According to his own recollections, these books had a significant influence on Nikolai Berdyaev, Vladimir Vernadsky, Ivan Bunin, and Alexei Tolstoy during their student years.[7][8][9]

According to Pavlenkov's plan, the series was intended to "acquaint readers with outstanding figures of the past". The word "remarkable," used in the title of the series, meant in the original sense "worthy of note, of attention, remarkable, extraordinary, or surprising. The first biography, published in late April or early May 1890, was that of Ignatius of Loyola.[10][11] Some of the most popular publications were Skabichevsky's essays on Lermontov and Pushkin; the last reprint of Pushkin's biography was dated 1924.[12] The series was based on the classical literary topos theory, which set forth ideas about the ideal of a creative person or a politician, inventor, etc. Ye. Petrova noted that most of the biographies corresponded to the normative ideals established in the XIX century, which were presented to the reader at the level of the title: "N (Dostoevsky, Laplace, Pirogov, Lincoln, etc.): his life and literary/state/scientific, etc. activities".[13] The new type of biographies, with the biographer's individual point of view and the ambiguity of the character's assessments, were less frequent; usually the construction of a personal image, rather than a system of topos, was undertaken at the turn of the century on the basis of psychological science and the general interest in the mental deviations of prominent people. Evgeny Solovyov, who wrote essays on Dmitri Pisarev, Ivan Turgenev, Alexander Herzen, Leo Tolstoy, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Nikolai Karamzin, Hegel, Oliver Cromwell, Osip Senkovsky, the Rothschild family, and Ivan the Terrible, was particularly fond of this approach. It was Solovyov who actively popularized Nikolai Mikhailovsky's formula "Dostoevsky is a cruel talent," but he did not refuse to consider the spiritual basis of the writer's interests. The concepts of "martyrdom", prophecy and genius in E. Solovyov's essay contributed to the popularization of the "Dostoevsky myth", which established a new system of normative rhetorical biography of the Soviet period.[14]

In 1916, Maxim Gorky tried to continue Pavlenkov's series on the basis of his own publishing house "Parus". He drew up a new plan of the library series, including almost 300 titles; the project was also proposed to Zinovii Grzhebin, but the revolutionary situation did not allow it to be realized. In 1921, independently of Gorky, the M. and S. Sabashnikov's publishing house started the series "Historical Portraits", in 1922 the cooperative publishing house "Kolos" published "Biographical Library". In 1923, the Brockhaus-Efron publishing house opened the series "Images of Mankind". In 1925 the series "Biographical Library" was founded by Gosizdat (Association of State Book and Periodical Publishers), and in 1928 the series "The Lives of Remarkable People" was published by Moskovsky Rabochiy publishing house, but in none of the series the number of published books did not exceed half a dozen.[15]

The Gorky Series (1930s–1980s)[edit]

A study by Ural literary scholars Tatiana Snigiryova and Alexei Podchinenov identifies three periods in the development of The Lives of Remarkable People series, designated by the iconic name of the publishing house: "The Pavlenkov Series" (1890–1900), "The Gorky Series" (1930–1980), and "The Molodaya Gvardiya Series" (from 1990–2000). In each of them the main features were different.[16]

1930-1940s[edit]

At the beginning of the 1930s, Maxim Gorky managed to realize his initial idea on the basis of the Journal-Gazette Association (Zhurgaz) led by Mikhail Koltsov. According to the surviving correspondence, Gorky tried to attract the best writers or specialists with a talent for writing to participate in a universal series of biographies: Romain Rolland received an order for a book on Socrates and Beethoven, Fridtjof Nansen for a biography of Columbus, Ivan Bunin for a biography of Cervantes, Anatoly Lunacharsky for a history of Francis Bacon, and Kliment Timiryazev for a book on Charles Darwin. In practice, the manuscripts received did not always suit the organizer of the series, who had a maximalist attitude and supervised the project until his death in 1936. The first issue of the series was published in January 1933, it was a biography of Heinrich Heine by Alexander Deitch, followed by biographies of Mikhail Shchepkin, Rudolf Diesel, Dmitri Mendeleev, Heinrich Pestalozzi, Ivan Sechenov, George Sand and the Wright brothers. The last book in the series published during Gorky's lifetime was a biography of Napoleon by Yevgeny Tarle. The writer bequeathed the series to the Komsomol, appealing to the General Secretary of the Komsomol Central Committee, Aleksander Kosarev. After the dissolution of Zhurgaz in 1938, the series was taken over by the "Molodaya Gvardiya" publishing house. Thus, the publication of biographical books was put at the service of education of new generations and was never interrupted. Despite the didactic character of the series, the concept of "remarkable" began to change in the use of the living word, approaching the words "outstanding" and even "great". Thus, among the first books published in the series were those about Napoleon, Talleyrand, the "shark of capitalism" Henry Ford, and even the conquistador Pizarro. Gorky believed that books about negative characters need the reader no less than books about positive ones. In 1934, the edition of Gogol's biography written by the exiled critic Alexander Voronsky was confiscated and destroyed, and it was not republished until 2009, on the occasion of the 200th anniversary of Gogol's birth. This book was the first in the "Small Series of The Lives of Remarkable People". In 1933, Gorky himself rejected Mikhail Bulgakov's biography of Molière for its "non-Marxist approach" and "excessive emphasis on the personal attitude to the subject"; the book was not published in the series until 1962.[15][17][18]

The publishing house created a public editorial board of the series, which included academicians Vladimir Komarov, Evgeny Tarle, Alexander Fersman, professors Yuri Tynyanov and Pavel Yudin, writers Alexander Fadeev and Alexei Tolstoy. The heroes of the books were mostly world-famous figures of science and art, as well as revolutionaries. By 1941, 107 books in the series had been published, with a total circulation of about 5 million copies. With the outbreak of World War II, the series was discontinued; in 1943, the biographical series began to be published under the name "Remarkable Russian People" (14 issues in total)[19] — small-format books that could be carried in a coat pocket.[20][21] From 1944 to 1945 the series was called "Remarkable Russian People" (28 books were published). Since 1945, the biographical series was published again under the old name "Remarkable People's Live".[19]

The average print run of the books of the series was 40–50 thousand copies with the usual volume of the book of 200 pages. From the very first editions, the cover had a pen-and-ink portrait of the book's hero, made according to the sketches of Peter Alyakrinsky, Grigory Bershadsky, Nikolai Ilyin. The format of the books gradually changed. The titles of the books in the series were standard: usually the surname or the first name and the surname of the character, less often (for Russian and Soviet people) the initials and the surname. Artistic titles were very rare. Biographies of Russian and foreign personalities were published about equally. Writers and poets (21 biographies), scientists (18 biographies), revolutionaries and reformers (18 biographies), inventors (14 biographies), travelers (8 biographies), and others were usually considered "remarkable".[22]

In the 1940s, after the resumption of the series, the publication rate of the series decreased: from 3 to 7 new books per year (before the war from 8 to 20), until 1949 only 53 biographies were published (and 7 reprints), but the average length of the text increased to 350 pages. The distribution of topics differed little from the prewar distribution: 14 biographies of writers, 11 of scientists, 7 of inventors, 5 of military leaders, 4 of travelers, etc. Between 1950 and 1959, 104 biographies were published, with an average print run of 56,000 copies, but their size varied greatly. After 1956, the number of books published and the size of the print runs returned to the pre-war figures. The number of reprints increased significantly to 27. In the 1950s, the most published biographies were biographies of writers and poets (27 biographies), scientists (27 biographies), revolutionaries and reformers (17 biographies).[23]

The Khrushchev Thaw's and the Stagnation's period[edit]

In the 1950s, the editors of the series formulated three main principles for the selection of published texts, which have been maintained ever since: scientific accuracy, high literary level, and entertainment.[20] The quality of writing about the founders of science and technology was so high that, according to the recollections of Igor and Lev Krupenikov, the book about Vasily Dokuchayev was used by students of the State Agrarian University of Moldova to prepare for the exam on soil science.[24] Gradually, the style and design principle of serial volumes were developed: in the early 1950s, the books were small, the cover had an engraved portrait in the form of a medallion, which in turn was inscribed in an oval organizing the entire cover. In the mid-1950s, the author was sometimes not credited on the cover at all (previously, the author could be credited first, then the hero, and vice versa).[25] In 1962, as a result of a competition, a standardized cover design (by the artist Yuri Arndt) was adopted. From then on, the binding was a photograph or other portrait of the person, supplemented with images (drawn or photographic) related to the life and activities of the hero. The emblem of the series, a golden torch as a symbol of enlightenment, created by the artist Boris Prorokov, was placed on the spine of the book from 1958. After 1962 the torch became white.[12]

During the Thaw, the series began to publish biographies of foreign authors: Stefan Zweig's books on Balzac, Irving Stone's books on Jack London ("Sailor in the Saddle" was the first book in the series to be published in a new design),[26] Carl Sandberg's books on Lincoln. A landmark was the publication of Mikhail Bulgakov's biography of Molière, written thirty years earlier. The number of annual issues of the series grew from 5–6 to 25–30, and their average circulation increased from 50 to 100 thousand. The record circulation of Vasily Kardashov's biography "Rokossovsky" (1972) was 300,000 copies, which was repeated in 1986 by the book about Yuri Gagarin (by Viktor Stepanov). The genre of biography was popular in the country, and various publishing houses published the series "Flaming Revolutionaries", "Life in Art", "Thinkers of the Past". According to M. Izmailova, the Soviet reading public, entering the period of intense spiritual search, tried to find role models in the figures of the distant and recent past, as well as to feel the contrast between their turbulent lives and their own "unheroic" reality. In this context, there was also a demand for other heroes: thinkers, patriots, luminaries of national culture.[27][28][26] In different years, "Molodaya Gvardiya" invited Anatoly Levandovsky, Lev Gumilevsky, Sergei Durylin, Konstantin Paustovsky, Marietta Shaginian, Korney Chukovsky, Yuri Lotman, Aleksei Losev, Nathan Eidelman, and many others to write biographies.[29]

After 1960, the series regularly published books about Latin American heroes: biographies of Bolivar, Pancho Villa, Miranda, Benito Juarez, Che Guevara, Salvador Allende. Their author (under the pseudonym "Lavretsky") was the Soviet intelligence officer and Latin American scholar Iosif Grigulevich. In 2002, his own biography, written by Neil Nikandrov, was published in the series. In a sense, the tone of the texts published in the 1960s–1970s was subordinated to the requirements of ideology, when the concept of "remarkable" was interpreted as "flawless". Most of the heroes chosen were ideologically upright and morally irreproachable, and very little was said about the difficulties of their destinies. In the volume "Olympians", the essay about Inga Artamonova ended very differently: "Her life ended too soon," without mentioning (as in the official obituaries) that the world champion speed skater was stabbed to death by her jealous husband. Essays on Civil War commanders were standard, concluding with their "tragic deaths" without reporting that they took place during the years of the Great Purge.[30] A biography of Nikolai Vavilov (by Semyon Reznik), published in 1968, generally omitted any mention of his arrest and death in prison, but its publication was nevertheless delayed to remove some passages exposing the Lysenkoism's members. Mark Popovsky called this "canonization with the cutting off of the biography".[31] In the collection "Young Heroes of the World War II", published in 1970, six of the forty heroes have no patronymics and years of life, and four of them even have no names; the author of the essays on young soldiers is also not specified.[32] The editorship of the series was sometimes severely criticized by the party structures. One of the most difficult periods was caused by the conflict between the publicist and writer Mikhail Lobanov and Alexander Yakovlev. This conflict provoked an attack on the book about A. N. Ostrovsky. Sometimes the thematic plans of the series "The Lives of Remarkable People" caused opposition in the press department of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Problems arose with the biographies of Andrei Rublev and even Yanka Kupala, who was accused of "bourgeois nationalism".[33] A complicated situation arose at the end of the 1970s with the biography of N. V. Gogol, which I. P. Zolotussky spent ten years writing. The publishers did not accept the manuscript and, according to him, the author even considered emigration. The situation was settled by the intervention of the First Secretary of the Board of the Union of Writers — G. M. Markov: after the 1979 edition, I.P. Zolotussky's book was published at least six times in the series.[34]

The post-Soviet period[edit]

With the end of the Soviet Union in 1991, the series faced not only economic but also socio-cultural changes in Russian society. Heroes of the Soviet past were overnight perceived as either criminals or victims, and their place was taken by previously unknown or forbidden figures: dissidents, tsars and dignitaries of pre-revolutionary Russia, and "stars" of mass culture. Due to the liquidation of most of the largest enterprises of the Soviet book publishing ("Molodaya Gvardiya" survived), the print editions decreased dramatically (to 10 and 5 thousand copies), which was connected with the decline in the prestige of reading and the high price of books. The most "failed" years were 1992 (two books of the series were published) and 1994 (one book). The genre of biographies for the mass public was monopolized by the mass media specialized in revealing scandalous details; then the Internet became a strong competitor. As a result, the genre of "classical" biography was confined within a scientific framework, and the tradition of romanticized hagiography effectively died out. Professional historians and philologists began to predominate among the authors of the series. All this led to the publication of highly specialized texts inaccessible to a wide audience. Along with the reduction of the periodicity of the series to a few books a year, the 1990s saw a tremendous expansion of its thematic scope: biographies of tsars, Orthodox saints, emigrant writers, and figures of the White Movement began to appear. The flow of translated literature, which met the needs of the mass audience in terms of actual personalities, increased significantly. The management of the series did not allow its closure neither the decrease of standards.[35][36]

The year 2005 marked a new stage in the development of the "The Lives of Remarkable People" series with the publication of the biography of Boris Pasternak by Dmitry Bykov. This book, which combines a popular presentation with a large number of facts, has been reprinted more than a dozen times and has significantly revived the interest of the reading public in the products of "Molodaya Gvardiya" and the biographical genre as a whole. The editorial staff began to attract contemporary writers to work with them again. According to M. I. Izmailova, the development of the series is taking place against the background of the coexistence of several trends in Russian biographical narrative, both familiar and more recent.[37] In 2008, RIA Novosti noted that "the current series "The Lives of Remarkable People" is unique: it has neither temporal nor geographical limits, its hero can be a person who acted in any field, without professional limitations".[19]

In 2001 the thousandth issue of the series was published (the biography of Vladimir Vernadsky by Gennady Aksyonov), in connection with which two jubilee exhibitions of the series were held in the State Duma of the Russian Federation and in the Presidential Library in the Kremlin. From that time on the numbering of the series was increased by 200 books by Pavlenkov, and on the frontispiece the inscription appeared: "A series of biographies. Founded in 1890 by F. Pavlenkov and continued in 1933 by M. Gorky".[26] The total circulation of the series exceeded 100,000,000 copies.[38][39] The 1500th issue of the series was the biography of Yuri Gagarin written by Lev Danilkin and published on the 50th anniversary of the first space flight.[40]

Reviews and opinions[edit]

Literary features of the "The Lives of Remarkable People" series biographies[edit]

The evolution of the series[edit]

Florentiy Pavlenkov published his series after having preliminarily defined the circle of characters and the ideological orientation (which was adjusted "from radicalism to enlightenment"). The genre format of the series was determined by the goals of enlightenment: a popular biographical sketch focusing on the great deeds of a man who left his mark on the history of world civilization. Maxim Gorky took into account Pavlenkov's experience, so the format he established had a clearly expressed cultural and ideological character. The history of "remarkable people" was not so much reconstructed as rewritten within the framework of Soviet ideological tasks. Cultural Revolution in the Soviet Union was based on the slogan "The country should know its heroes".[41]

Alexei Varlamov called the genre of biographies of the Gorky period "memorial books". Such biographies were commissioned from well-known and authoritative scholars and writers who could delve deeply into the fate and work of the hero, including his spiritual biography. He mentions Yuri Seleznyov's book on Dostoevsky (first edition 1981) as a reference. Its main plot is "the writer's journey through life, his 'self-defense' and confrontation with external circumstances". The division of the book into parts is strictly ternary: "The Fate of Man", "The Life of a Great Sinner", "The Life and Death of a Prophet", divided into chapters: "Golgotha", "Porposch", "Temptation" (Part One), chapters in subchapters: "Wharf", "Abysses", "Beauty Will Save the World" (chapter three of part two).[42] In general, the revelation of new facts and the enrichment of historiography periodically led the editors to order new biographies of the same people. An example is Fyodor Dostoevsky himself (Lev Grossman's book was published as early as 1962). The biographies of Esenin and Mayakovsky and other writers were subjected to creative interpretation.[43]

There is no unified strategy at the present stage of the publishing series, which has been carried out since the 1990s. It can be partly described as "commercial", which is reflected both in the quality of some books and in private publishing practices: it is aimed at the mass reader and commercial success, and is influenced by the technologies of modern popular culture. "The magisterial intrigue of a story about an interesting but not necessarily remarkable person is often built on plots of exposure, gossip gathering, and mystery solving. Nevertheless, the series continues to fulfill its enlightening, cultural, and social (myth-making) functions. The format's ambiguity provides more freedom for creative and research experiments; both literary studies (a book on Anna Akhmatova by Svetlana Kovalenko, a book on Daniil Kharms by Alexander Kobrinsky, a book on Osip Mandelstam by Oleg Lekmanov, a book on Samuil Marshak by Matvei Geyser, a book on Valery Bryusov by Nikolai Ashukin and Ruslan Shcherbakov), and the "literary novel" (Alexei Varlamov's books on Alexei Tolstoy, Mikhail Prishvin, Alexander Grin, Mikhail Bulgakov; Pavel Basinsky on Gorky; Dmitry Bykov on Boris Pasternak, Bulat Okudzhava).[42] Traditionally, each book of the series is completed by a section "Main dates of life and work", but more often the chronology in these books is manifested on the level of fabula, while the narrative strategy is based on the plot intrigue, presented in the prologue author's plot twist.[44] The book about Federico Fellini is a collection of interviews with the director conducted over forty years by the journalist Costanzo Costantini; the editor's preface emphasizes the break with the usual form of presentation.[45]

Writer Alexander Shelukhin has made a statistical count of the number of books in the series, including reprints. His proposed five-part tentative chronology is the following:[32]

- 1890–1924 (including a five-year hiatus during the Civil War): 242 books, averaging 7 per year;

- 1933–1953 (counting a two-year hiatus during World War II): 183 books, 9 per year;

- 1954–1991: 645 books, 17 per year;

- 1992–1999: 50 books, 6 per year;

- 2000–2021: 1,188 books or 54 issues per year.

Sub-series of "The Lives of Remarkable People"[edit]

In 2005, Valentin Yurkin, the editor-in-chief of the series and the general director of the publishing house "Molodaya Gvardiya", decided to start the cycle "Lives of Remarkable People. Biography continues". The first issue was dedicated to Boris Gromov, the governor of the Moscow region. It was presented as a revival of another Pavlenkov tradition: in the series "The Lives of Remarkable People of the 19th century" were published biographies of Leo Tolstoy, Otto Bismarck and William Gladston. In the series "Gorky" the living "remarkable people" could appear only in collections. Critics linked the publication of this biography to the upcoming 2008 presidential election, calling the publication "fictitious capital".[46] The series continued with books on Mintimer Shaimiev and Nursultan Nazarbayev, which made extensive use of interviews and memoirs by the figures themselves, their associates, friends and relatives.[47]

In 2009, the "Small Series of The Lives of Remarkable People" was launched. According to Pavel Basinsky, it was a response to the challenges of the new times, anticipating the current economic crisis and the related crisis in book publishing. The publisher's calculation was to create similarly designed compact books, suitable for reading on the road or in the subway. This format is much more difficult for the author, as the volume of the book should not exceed 8 or 10 printed pages. It was originally planned that biographies of the same heroes would not be duplicated in the small and main series,[48] but the main series in 2020 included a biography of Gogol written by A. K. Gogol. К. Voronsky,[49] and in August 2022 a biography of A. S. Pushkin, prepared by V. I. Novikov,[50] was published in the same way. I. Novikov.[50] Initially, both books were published in the "Small Series of The Lives of Remarkable People".

Later, the series "The Lives of Remarkable People: Modern Classics"[51] and "The The Lives of Remarkable People: Great People of Russia".[52]

The style of the books series[edit]

For many years the books of the series "The Lives of Remarkable People" caused a great excitement in the reading and academic circles. As Galina Ulyanova, Doctor of Historical Sciences, noted: "The series was a very bright phenomenon in the public life of the 1960s and 1970s. Huge print runs of up to 100 thousand copies, supplements with illustrations. For any author, writing a book for this series was a recognition of his or her high professional level".[53] Many of the books in this series still receive positive reviews from professional critics.[54]

The Russian historian Sergei Firsov characterizes the style of the books published in this series in the following way:

... the books of this series have several directions. Some of them can be called literary-fictional, others historical-publicistic, and even scientific-historical. One thing is unchangeable: a book published in the "The Lives of Remarkable People" series must be written in such a way that a reader interested in history can read it with no less interest than a professional researcher familiar with historical questions. Of course, much depends on the ability of the author: some are able to speak simply and clearly about the complex, while others do not have it.[55]

In the research of Angelina Terpugova (Institute of Linguistics of the Russian Academy of Sciences) all texts of the series were analyzed by chapter titles. It turned out that the structure of biographies is subordinated not only to the factual framework (birth, studies, work, death), but also reflects stable ideas about a "remarkable person" (hero). The structure of the table of contents always contains elements related to the singularity of the "remarkable person" (vocation, fateful encounter, miracle, struggle, trial, etc.). These elements are repeated in all the books of the series without exception. According to Angelina Terpugova, this is due to stereotypical ideas about "remarkable people", the carriers of which are both authors and readers.[56]

Critics[edit]

Literary criticism[edit]

Despite their popularity among the public and specialists, the books of the "The Lives of Remarkable People" series have been repeatedly criticized for lack of objectivity and partisanship. Oleg Osovsky (to be confirmed) conducted a special study of this situation. He noted that as of 2018, interest in the series has somewhat decreased, which is indicated by the modest circulation of most books, although some publications became an event and caused serious polemics among literary critics and literary critics. It is also due to the fact that the general reading public is not interested in the biographies of scientists in their achievements, but focuses on small everyday details and weaknesses of the personality. For example, Boris Egorov's biography of Juri Lotman was called "an achievement of the subgenre of scientific biography", but it was never published in the series. This is also explained by the fact that there is a natural contradiction between the author of a literary biography and a literary study, the general meaning of which can be expressed by the formula "literary VS: documentary".[57] In his time, Mikhail Bakhtin refused to use the biographical method in his studies of Rabelais and Dostoevsky, noting that "our biography is some mixture of creativity and life. Dostoevsky, like any writer, is one person in his work and another in his life. And how these two people (the creator and the simple man of life) are combined is still not clear".[58] The authors of the series have bridged this gap ("person of life" and "person of art") in different ways. As an example, the biographies of Dmitry Likhachev (by Valery Popov), Viktor Shklovsky (by Vladimir Berezin), and Mikhail Bakhtin (by Alexei Korovashko), authored by a professional writer and two literary critics, were cited. As a result, according to Oleg Osovsky, in the book about Likhachev the author tries to define his contribution to Russian culture "with the help of a set of not at all literary stamps and clichés" (for example, drawing analogies with A. Solzhenitsyn), while the literary scholars Vladimir Berezin and Alexei Korovashko tried to "color" the historical-literary text "with inclusions of fine diction".[59]

The analyzed authors tried to use actively the memoir prose of Likhachev, Shklovsky and Bakhtin themselves in the biographies of their heroes. Valery Popov, who used the memoirs of Academician D. Likhachev to narrate the facts of his life, did not try to recreate the inner world of his hero, especially since the genre of biography, as a writer, spared him the task of artistic narrative. On the contrary, Viktor Shklovsky's memoir prose of the 1960s closely correlated and polemicized with his own prose of the 1920s, forcing the researcher to turn to a set of literary devices that characterize both the style and the thinking of the hero. "V. S. Berezin's book may seem overly complicated and stylistically sophisticated to the average consumer of the series, but it must be recognized that the author generally remained within the conventional boundaries of the genre".[60]

On the contrary, in A. V. Korovashko's book his character Mikhail Bakhtin appears as an "antihero". The series of "The Lives of Remarkable People" was initially characterized by a clear tendency to "panegyric" biography, in which the author not only believes in the "remarkable" character of his hero, but also considers him to be a model. In the case of Mikhail Bakhtin, the biographer's task was to fight the "Bakhtin myth," which manifested itself, among other things, in the form of "aggressive distrust" of the memoirs of Bakhtin himself and his closest circle. At the same time, in O. Osovsky's opinion, Korovashko made gross mistakes and did not handle the used texts very correctly, since the genre of popular biography does not require references to the cited literature. Apparently, the author did not understand the scientific views of Mikhail Bakhtin. On this material O. Osovsky came to the conclusion that biography is a relatively conservative genre in which the established schemes and techniques of narration are maximally justified, while attempts to modify the established strategy of the biographer leads to the loss of literary character and replacement of factuality with fiction and conjecture.[61]

The failures of the popular series[edit]

Critical remarks were also made about other books in the series. Thus, the granddaughter of Leonid Andreev, Irina Andreeva, spoke extremely negatively about the biography of her grandfather.[62] On the biography of Ivan Yefremov his granddaughter – the sculptor D. Efremova expressed as an "order to dehumanize"; her interview caused a lot of harsh comments.[63] Earlier, a negative review of the same biography was published by the writer and literary critic Valery Teryokhin.[64] The biographies of Alexander III[65] and Buddha[66] were harshly criticized, the biographies of Homer,[67] Velimir Khlebnikov[68] and Patriarch Sergius[55] were not highly praised, the biographies of Andrei Platonov,[69] Yuri Andropov,[70] Samuel Marshak,[71] Kornei Chukovsky[72] and Viktor Tsoi[73] were ambivalently received. Vladimir Shukhov's great-granddaughter called her great-grandfather's biography "a disgusting book, illiterate, unscrupulous and talentless". The "Molodaya Gvardiya" publishing house itself released an official refutation of this attack.[74]

The biography of Jesus Christ written by Metropolitan Hilarion (Alfeyev) caused a well-known resonance. The author considered it a popular version of the great six-volume monograph "Jesus Christ. Life and Teachings". Its publication in the series was justified as follows: "He was God, which did not prevent him from being a man: an interesting and intelligent one".[75] Ecclesiastical and secular critics made diametrically opposed assessments. In particular, the rector of the Minsk Theological Academy Sergius (Akimov) called the book "an excellent manual on homiletics and the history of the Gospel for theological schools",[76] Georgy Orekhanov, Vice Rector of the Saint Tikhon's Orthodox University, called the book "useful in terms of disseminating adequate views of Christianity" to a wide audience, and historian Dmitry Volodikhin considered that the task had been accomplished "to tell unchurched people in good Russian literary language who Jesus was".[77] It has also been said that this book is evidence of "profanation of the sacred and secularization of Christianity, forced adaptation of the Church of Christ to the world for the sake of imaginary 'missionary' goals".[78]

According to science fiction critic Roman Arbitman, the publishing house planned to publish a biography of the Strugatsky brothers, written by science fiction writer Ant Skalandis, in the series. The conflict with the editors arose because of a detailed review of the vicissitudes that took eight years to publish the story "Roadside Picnic" in "Molodaya Gvardiya" in the 1970s. As a result, Skalandis' voluminous volume was published by AST (and again received harsh reviews, especially for "self-expression at the expense of the characters").[79] The contract for a new biography of half the volume was signed with Gennady Prashkevich and Dmitry Volodikhin. Roman Arbitman accused the authors -a professional novelist and historian- of a consistent conspiracy theory and an attempt to "marginalize their heroes". It was also noted the poor quality of the editorial work, because of which the first edition was full of factual errors, for example, the 20th and 22nd Congresses of the CPSU were mixed up.[80]

In 2010, a complicated situation arose with the publication of Dovlatov's biography, written by Valery Popov. The book was published without the traditional photo of the protagonist on the cover, which was replaced by the inscription: "Here should have been a portrait of S. Dovlatov". This was due to the fact that the heirs forbade the reproduction of any photographs of the writer and most of the texts of his letters.[81][82]Alexander Shelukhin, given the enormous number of biographies published in the series after 2000 (an average of 54 books per year), criticized the selection of characters in the books. By the end of 2021, the series had published 2173 biographies, of which 161 were women, i.e. there was a gender disproportion (in the critic's terminology, "patriarchal"). Russian (Soviet) personalities: 1381 men and 116 women. In total, personalities from 72 countries are represented in the series. According to the number of names presented in the series, after Russia, France is the leader: 122 people, then Great Britain and the US: 79 each, Germany: 60, Italy: 58, Greece: 17, Spain: 15, Poland: 11. Chinese personalities: eight, Latvian three (all from the USSR period). In 2019–2021, 230 biographies will appear in the "The Lives of Remarkable People" series, including a book on all Byzantine emperors and one on US presidents. At the same time, the only major country that is not represented in the series at all is Japan. A. Shelukhin ironically pointed out that the series lacks a biography of Nobel Prize winner Pyotr Kapitsa, although there is a book about his son, and listed other "gaps" in the list of personalities. Also, from the critic's point of view, some characters with their qualities are clearly "drawn by the ears", including Ivan Antonovich and Anna Leopoldovna, who "did not show themselves in any way".[32]

The literary critic Sergei Belyakov explicitly stated it:[83]

"The publishing house "Molodaya Gvardiya" is exploiting a gold mine of the "The Lives of Remarkable People" series. The books are published in such large numbers and in such an astonishing range (from Johann Wolfgang Goethe to Eduard Streltsov) that the publishing house apparently does not even spend precious time on the most modest editing. And they do!"

Awards[edit]

- In 2003, Pierre Ciprio's biography "Balzac Unmasked" received the "Abzats" anti-award. The reason was a failure to meet the standards accepted in Russian literary studies: the translator, Evgenia Sergeeva, did not always accurately reproduce the traditional translations of the titles of Balzac's novels.[84]

- The books of the series won three times in a row in the competition of the National Literary Big Book Award (2006: "Boris Pasternak" by Dmitry Bykov, 2007: "Alexei Tolstoy" by Alexei Varlamov, 2008: "Solzhenitsyn" by Lyudmila Saraskina).

- The National Prize "Best Books and Publishers of 2010" was awarded to Valentin Osipov's book "Sholokhov".

- The Patriarchal Prize was awarded to the books "Metropolitan Filaret" and "Alexis II" by Alexander Segeny.

- А. M. Turkov was awarded the Governmental Award of the Russian Federation (2012) for his biography of A. Tvardovsky.[85]

The "The Lives of Remarkable People" content[edit]

Florentiy Pavlenkov's series, 1890—1924[edit]

- Main article: "The Lives of Remarkable People"

The "The Lives of Remarkable People" after 1933[edit]

Additional series[edit]

- Main article: "The Lives of Remarkable People. Biography continues"

- Main article: "The Lives of Remarkable People. Small series"

- "The Lives of Remarkable People. Modern classics"

- "The Lives of Remarkable People. Remarkable Russian People".

References[edit]

- ^ Мильчин А. Э. Издательский словарь-справочник. — 2-е изд., испр. и доп. — М.: ОЛМА-Пресс, 2003. — P. 33. — 560 p.

- ^ Белякова Г. В., Гаврилкина Т. Ю. Об особенностях произношения русских аббревиатур // Альманах современной науки и образования. — 2016. — № 11 (113). — P. 12—14.

- ^ Баталина Ю. Человеческие истории. Электронное периодическое издание «Новый Компаньон». РИА ИД «Компаньон» (4 September 2007).

- ^ Юркин В. Ф. Энергия сопротивления. Издательство «Молодая гвардия»: XXI век. Осмысление прошлого, приближение будущего / сост. С. Г. Коростелев. — М.: Молодая гвардия, 2019. — 489 p.

- ^ «МОЛОДА́Я ГВА́РДИЯ» : [арх. 21 октября 2020] // Меотская археологическая культура — Монголо-татарское нашествие. — М. : Большая российская энциклопедия, 2012. — P. 686. — (Большая российская энциклопедия : [in 35 volumes.] / гл. ред. Ю. С. Осипов; 2004—2017, v. 20). — ISBN 978-5-85270-354-5.

- ^ Вишнякова Ю. И. Воспитание на образце: 80 лет биографической серии «Жизнь замечательных людей» издательства «Молодая Гвардия» // Вестник ПСТГУ. Серия IV: Педагогика. Психология. — 2019. — Iss. 53. — С. 122.

- ^ Каталог «ЖЗЛ». 1890—2002 / Сост. Л. П. Александрова, Е. И. Горелик, Р. А. Евсеева. — 4-е изд., испр. и доп. — М.: Молодая гвардия, 2002. — P. 5.

- ^ Альманах библиофила. — Т. 18. — М.: Книга, 1985. — С. 273.

- ^ Эрлихман В. В. ЖЗЛ: замечательные люди не умирают // Россия и современный мир. — 2012. — № 2. — P. 214.

- ^ Эрлихман В. В. ЖЗЛ: замечательные люди не умирают // Россия и современный мир. — 2012. — № 2. — P. 213.

- ^ Вишнякова Ю. И. Воспитание на образце: 80 лет биографической серии «Жизнь замечательных людей» издательства «Молодая Гвардия» // Вестник ПСТГУ. Серия IV: Педагогика. Психология. — 2019. — Iss. 53. — P. 122-123.

- ^ a b Вишнякова Ю. И. Воспитание на образце: 80 лет биографической серии «Жизнь замечательных людей» издательства «Молодая Гвардия» // Вестник ПСТГУ. Серия IV: Педагогика. Психология. — 2019. — Iss. 53. — P. 124.

- ^ Петрова Ю. В. Образ «Великого писателя» в неклассической биографической парадигме: биографии Достоевского конца XIX в. // Вестник Омского университета. — 2012. — № 1. — P. 269.

- ^ Петрова Ю. В. Образ «Великого писателя» в неклассической биографической парадигме: биографии Достоевского конца XIX в. // Вестник Омского университета. — 2012. — № 1. — P. 269-270.

- ^ a b Каталог «ЖЗЛ». 1890—2002 / Сост. Л. П. Александрова, Е. И. Горелик, Р. А. Евсеева. — 4 edition, испр. и доп. — М.: Молодая гвардия, 2002. — P. 6.

- ^ Снигирева Т. А., Подчиненов А. В. Литературная биография: традиция и современные интерпретационные стратегии // Интерпретация текста: лингвистический, литературоведческий и методический аспекты. — 2010. — № 1. — P. 97.

- ^ Эрлихман В. В. ЖЗЛ: замечательные люди не умирают // Россия и современный мир. — 2012. — № 2. — P. 214-215.

- ^ Вишнякова Ю. И. «ЖЗЛ»: издательская политика в первые десятилетия существования серии (1933—1959) // Румянцевские чтения — 2019. Материалы международной научно-практической конференции: в 3 частях. — 2019. — P. 129.

- ^ a b c Прошлое и настоящее серии «Жизнь замечательных людей». Справка. РИА Новости (20 April 2008).

- ^ a b Каталог «ЖЗЛ». 1890—2002 / Сост. Л. П. Александрова, Е. И. Горелик, Р. А. Евсеева. — 4-е изд., испр. и доп. — М.: Молодая гвардия, 2002. — P. 7.

- ^ Эрлихман В. В. ЖЗЛ: замечательные люди не умирают // Россия и современный мир. — 2012. — № 2. — P. 215.

- ^ Вишнякова Ю. И. «ЖЗЛ»: издательская политика в первые десятилетия существования серии (1933—1959) // Румянцевские чтения — 2019. Материалы международной научно-практической конференции: в 3 частях. — 2019. — P. 130-131.

- ^ Вишнякова Ю. И. «ЖЗЛ»: издательская политика в первые десятилетия существования серии (1933—1959) // Румянцевские чтения — 2019. Материалы международной научно-практической конференции: в 3 частях. — 2019. — P. 131-132.

- ^ Великие имена: «Жизнь замечательных людей» (85 лет серии популярных биографий): библиографический указатель лит. / отв. за вып. В. П. Карнаухова ; сост. Т. А. Сергеева ; оформ. обл. Т. С. Лаздовская. — Строитель, 2018. — P. 9.

- ^ Великие имена: «Жизнь замечательных людей» (85 лет серии популярных биографий): библиографический указатель лит. / отв. за вып. В. П. Карнаухова ; сост. Т. А. Сергеева ; оформ. обл. Т. С. Лаздовская. — Строитель, 2018. — P. 8.

- ^ a b c Великие имена: «Жизнь замечательных людей» (85 лет серии популярных биографий): библиографический указатель лит. / отв. за вып. В. П. Карнаухова ; сост. Т. А. Сергеева ; оформ. обл. Т. С. Лаздовская. — Строитель, 2018. — P. 10.

- ^ Эрлихман В. В. ЖЗЛ: замечательные люди не умирают // Россия и современный мир. — 2012. — № 2. — P. 217-218.

- ^ Измайлова М. И. Историческая биография: опыт и закономерности (на примере серии «ЖЗЛ») // Царскосельские чтения. — 2014. — V. 1, № XVIII. — P. 66.

- ^ Эрлихман В. В. ЖЗЛ: замечательные люди не умирают // Россия и современный мир. — 2012. — № 2. — P.216.

- ^ Эрлихман В. В. ЖЗЛ: замечательные люди не умирают // Россия и современный мир. — 2012. — № 2. — P. 217.

- ^ Поповский М. Дело академика Вавилова. — М.: Книга, 1991. — P. 278. — 304 p.

- ^ a b c Шелухин А. В Японии нет замечательных людей!? О некоторых нелепостях, казусах и курьёзах серии книг «ЖЗЛ» // Литературная Россия. — 2022. — № 1.

- ^ Эрлихман В. В. ЖЗЛ: замечательные люди не умирают // Россия и современный мир. — 2012. — № 2. — P. 230.

- ^ Малышев И. Возрождение через Гоголя // Литературная газета. — 2020. — 25 November (№ 47 (6762)). — P. 10.

- ^ Измайлова М. И. Историческая биография: опыт и закономерности (на примере серии «ЖЗЛ») // Царскосельские чтения. — 2014. — V. 1, № XVIII. — P. 66-67.

- ^ Прошлое и настоящее серии «Жизнь замечательных людей». Справка. РИА «Новости» (20 April 2008).

- ^ Измайлова М. И. Историческая биография: опыт и закономерности (на примере серии «ЖЗЛ») // Царскосельские чтения. — 2014. — V. 1, № XVIII. — P. 67.

- ^ Каталог «ЖЗЛ». 1890—2002 / Сост. Л. П. Александрова, Е. И. Горелик, Р. А. Евсеева. — 4-е изд., испр. и доп. — М.: Молодая гвардия, 2002. — P. 7-8.

- ^ Колпаков Леонид. «ЖЗЛ» расшифровывает чёрные ящики истории. Литературная газета (29 March 2017).

- ^ Эрлихман В. В. ЖЗЛ: замечательные люди не умирают // Россия и современный мир. — 2012. — № 2. — P. 218.

- ^ Снигирева Т. А., Подчиненов А. В. Литературная биография: традиция и современные интерпретационные стратегии // Интерпретация текста: лингвистический, литературоведческий и методический аспекты. — 2010. — № 1. — P. 97—98.

- ^ a b Снигирева Т. А., Подчиненов А. В. Литературная биография: традиция и современные интерпретационные стратегии // Интерпретация текста: лингвистический, литературоведческий и методический аспекты. — 2010. — № 1. — P. 99.

- ^ Великие имена: «Жизнь замечательных людей» (85 лет серии популярных биографий): библиографический указатель лит. / отв. за вып. В. П. Карнаухова ; сост. Т. А. Сергеева ; оформ. обл. Т. С. Лаздовская. — Строитель, 2018. — P. 13.

- ^ Снигирева Т. А., Подчиненов А. В. Литературная биография: традиция и современные интерпретационные стратегии // Интерпретация текста: лингвистический, литературоведческий и методический аспекты. — 2010. — № 1. — P. 100.

- ^ Николай Кириллов. В одном из неснятых фильмов Федерико Феллини. Частный корреспондент (14 April 2010).

- ^ Е. Лесин. Громов и пустота. Независимая газета (27 May 2005).

- ^ Косыгин Р. До новой встречи, Братислава! Международная жизнь, 2016, № 12. МИД РФ, Редакция журнала «Международная жизнь».

- ^ Басинский П. Святые и грешные. Интернет-портал «ГодЛитературы.РФ» (15 March 2015).

- ^ Гоголь. «Жизнь замечательных людей». АО «Молодая гвардия».

- ^ a b Александр Пушкин. АО «Молодая гвардия. «Жизнь замечательных людей».

- ^ «ЖЗЛ»: Современные классики».

- ^ «ЖЗЛ: Великие люди России».

- ^ Галина Ульянова. Наталия Михайловна Пирумова (1923—1997): судьба историка в зеркале эпохи. К 90-летию со дня рождения.

- ^ Афиша Воздух: ЖЗЛ Артюра Рембо, «Русско-еврейский Берлин» и другие книги — Архив. Афиша.

- ^ a b Фирсов С. Л. Личность, политика и власть. О книге М. И. Одинцова «Патриарх Сергий» // Церковь и время. — 2013. — № 1 (62). — P. 211-243.

- ^ Терпугова А. В. Оглавление книг серии «Жизнь замечательных людей» как особый предмет рассмотрения // Вестник Новосибирского государственного университета. Серия: Лингвистика и межкультурная коммуникация. — 2011. — V. 9, issue 2. — P. 76.

- ^ Осовский О. Е. «Литературность» против документальности как авторская стратегия в современной биографии (на материале последних изданий серии «ЖЗЛ») // Филология и культура. — 2018. — № 3 (3). — P. 195.

- ^ Осовский О. Е. «Литературность» против документальности как авторская стратегия в современной биографии (на материале последних изданий серии «ЖЗЛ») // Филология и культура. — 2018. — № 3 (3). — С. 195–196.

- ^ Осовский О. Е. «Литературность» против документальности как авторская стратегия в современной биографии (на материале последних изданий серии «ЖЗЛ») // Филология и культура. — 2018. — № 3 (3). — P. 196.

- ^ Осовский О. Е. «Литературность» против документальности как авторская стратегия в современной биографии (на материале последних изданий серии «ЖЗЛ») // Филология и культура. — 2018. — № 3 (3). — P. 195-197.

- ^ Осовский О. Е. «Литературность» против документальности как авторская стратегия в современной биографии (на материале последних изданий серии «ЖЗЛ») // Филология и культура. — 2018. — № 3 (3). — P. 197.

- ^ «Желтый смех» по Леониду Андрееву. Московский комсомолец.

- ^ Коротков Игорь. Соцзаказ на расчеловечивание Что мы не знаем о великом фантасте Иване Ефремове? Литературная Россия (10 October 2019).

- ^ Терёхин Валерий. Успехи и… неудача. О книге Ольги Ерёминой и Николая Смирнова об Иване Ефремове. День Литературы — газета русских писателей (12 January 2015).

- ^ gorky.media. Антисемитизм, боязнь террора и любовь к сушкам. «Горький» (5 October 2016).

- ^ Нирвана нашла своего героя (англ.). www.ng.ru.

- ^ Летнее чтение. Грибная философия, ЖЗЛ Гомера и Ленина, история хип-хопа и тайны мёртвых композиторов. Инде

- ^ Призрак Председателя. Газета.Ru.

- ^ Гришин А. Тайна за семью печатями. Воронежская областная универсальная научная библиотека им. И. С. Никитина. Литературная карта Воронежской области (2011).

- ^ Владимир Домбровский. На голубом глазу Андропов. Газета.Ru (2 October 2006).

- ^ Рецензия на книгу Матвея Гейзера «Маршак» (М.: Молодая гвардия, 2006. Сер. «Жизнь замечательных людей»). Новосибирская областная детская библиотека им. А. М. Горького.

- ^ Иванова Е. «Зимний взят и загажен», или Новый биографизм в стиле ток-шоу (Рец. на кн.: Лукьянова И. Корней Чуковский. М., 2006). Новое литературное обозрение, 2008, № 2. Горький Медиа. Сетевое издание «Горький»

- ^ Лев Оборин. Виталий Калгин — «Виктор Цой» (10 апреля 2015). Дата обращения: 16 June 2017.

- ^ Осторожно, клевета! gvardiya.ru. Дата обращения: 8 February 2019.

- ^ Елена Яковлева. В серии ЖЗЛ вышла книга «Иисус Христос». Российская газета (13 February 2019).

- ^ Возможно ли написать биографию Иисуса Христа? Рецензия на книгу митрополита Илариона «Иисус Христос. Биография» в серии ЖЗЛ. Издательский дом «Познание».

- ^ Геннадий Окороков. Книжная биография Иисуса Христа расскажет неизвестные подробности его жизни. Вечерняя Москва. «Центр поддержки отечественной словесности» (13 February 2019).

- ^ Николай Каверин. О замечательных книгах из серии «Жизнь замечательных людей» одного замечательного митрополита: продолжение следует? Благодатный огонь. Православный журнал (20 September 2020).

- ^ В. Шубинский. Ант Скаландис. Братья Стругацкие. Colta.ru. OpenSpace.ru (3 July 2008).

- ^ Арбитман Р. Сторожа братьям нашим. Лехаим, № 4 (240). ЛЕХАИМ — ежемесячный литературно-публицистический журнал и издательство (April 2012).

- ^ Биография Довлатова вышла в «ЖЗЛ» к годовщине со дня смерти писателя. РИА Новости (24 August 2010).

- ^ Наринская Анна. Беспортретное сходство. «Довлатов» Валерия Попова в серии ЖЗЛ. Коммерсантъ, 2010, № 52 (20 August 2010).

- ^ Сергей Беляков. Смерть героя. Частный корреспондент (5 November 2012).

- ^ Л. Новикова. В «Книгах России» нашли опечатки. Коммерсантъ (18 March 2003).

- ^ Авдеев вручил премии правительства деятелям культуры. РИА Новости (3 March 2012).

Bibliography[edit]

- Великие имена: «Жизнь замечательных людей» (85 лет серии популярных биографий): библиографический указатель лит. / отв. за вып. В. П. Карнаухова; сост. Т. А. Сергеева ; оформ. обл. Т. С. Лаздовская. — Строитель, 2018. — 180 p.

- Вишнякова Ю. И. Воспитание на образце: 80 лет биографической серии «Жизнь замечательных людей» издательства «Молодая Гвардия» // Вестник ПСТГУ. Серия IV: Педагогика. Психология. — 2019. — issue 53. — P. 120—132.

- Вишнякова Ю. И. «ЖЗЛ»: издательская политика в первые десятилетия существования серии (1933—1959) // Румянцевские чтения — 2019. Материалы международной научно-практической конференции: в 3 частях. — 2019. — P. 129—134.

- Измайлова М. И. Историческая биография: опыт и закономерности (на примере серии «ЖЗЛ») // Царскосельские чтения. — 2014. — V. 1, № XVIII. — P. 64—68.

- Каталог 1933—1973. 40 лет ЖЗЛ / Редакторы-составители А. И. Ефимов, С. Е. Резник. — М.: Молодая гвардия, 1974. — 288 p.

- Каталог «ЖЗЛ». 1890—2002 / Сост. Л. П. Александрова, Е. И. Горелик, Р. А. Евсеева. — 4-е изд., испр. и доп. — М.: Молодая гвардия, 2002. — 328 p. — ISBN 5-235-02538-5.

- Каталог «ЖЗЛ». 1890—2010 / Составитель Е. И. Горелик. 5-е изд., испр. и доп. — М.: Молодая гвардия, 2010. — 432 p. — ISBN 978-5-235-03337-5.

- Осовский О. Е. «Литературность» против документальности как авторская стратегия в современной биографии (на материале последних изданий серии «ЖЗЛ») // Филология и культура. — 2018. — № 3 (3). — P. 194—198.

- Петрова Ю. В. Образ «Великого писателя» в неклассической биографической парадигме: биографии Достоевского конца XIX в. // Вестник Омского университета. — 2012. — № 1. — P. 268—270.

- Подчиненов А. В., Снигирёва Т. А. Литературная биография: документ и способы его включения в текст // Филология и культура. — 2012. — № 4 (30). — P. 152—155.

- Подчиненов А. В. Серия «Жизнь замечательных людей» в историческом и социокультурном аспектах // Научное и культурное взаимодействие на пространстве СНГ в контексте развития книгоиздания, книгообмена и науки о книге: материалы Международной научной конференции, Москва, 24—25 ноября 2014 г.: К 300-летию Библиотеки академии наук: part 1. — М.: Наука; Кн. культура, 2014.

- Снигирева Т. А., Подчиненов А. В. Литературная биография: традиция и современные интерпретационные стратегии // Интерпретация текста: лингвистический, литературоведческий и методический аспекты. — 2010. — № 1. — P. 97—101.

- Терпугова А. В. Оглавление книг серии «Жизнь замечательных людей» как особый предмет рассмотрения // Вестник Новосибирского государственного университета. Серия: Лингвистика и межкультурная коммуникация. — 2011. — V. 9, iss. 2. — P. 66—74. — ISSN 1818-7935.

- Шелухин А. В Японии нет замечательных людей!? О некоторых нелепостях, казусах и курьёзах серии книг «ЖЗЛ» // Литературная Россия. — 2022. — № 1.

- Эрлихман В. В. ЖЗЛ: замечательные люди не умирают // Россия и современный мир. — 2012. — № 2. — P. 213—223.

External links[edit]

- Weekdays and holidays of the Library-Museum "The Lives of Remarkable People" in Kurgan. JSC "Molodaya Gvardiya" (9 October 2020).

- In Kurgan the Library-Museum "The Lives of Remarkable People"was opened. Internet portal "GodLiterature. RF" (8 November 2017).

- "The Lives of Remarkable People". Catalog of books. "Molodaya Gvardiya".

- Interesting facts about "The Lives of Remarkable People" book series. Diletant (11 April 2016).

- Catalog of books edited in "The Lives of Remarkable People" series.

- Kolpakov Leonid. "The Lives of Remarkable People" decodes the black boxes of history. Literaturnaya Gazeta (29 March 2017).

- Lukyanova Irina. We were not standing here. Novoye Literaturnoye Obozreniye (2009, No. 1).

- Series page. Fiction Lab. Date of circulation: 3 November 2020.