Slavery in the Umayyad Caliphate

| Part of a series on |

| Slavery |

|---|

|

Slavery in the Umayyad Caliphate refers to the chattel Slavery taking place in the Umayyad Caliphate (661–750), which comprised the majority of the Middle East with a center in the capital of Damascus in Syria.

The slave trade in the Umayyad Caliphate was massive and expanded in parallell with the Umayyad Imperial conquests, when non-Muslim war captives as well as civilians were enslaved, and humans were demanded by tribute and taxation from subjugated people. The slave trade was a continuation of the slave trade of the preceeding Rashidun Caliphate except in size, which was parallelled by the massive Imperial conquests.

When the governing elite of the Caliphate established a permanent urbanized residence, the institution of slavery expanded in parallell with the growing access as well as the needs of a new urbanised and more sophisticated state apparatus. The system of harem sexual slavery, as well as military slavery of male slaves, expanded during this period, though they would not be fully developed until the succeeding Abbasid Caliphate.

Slave trade[edit]

The slave trade in the Umayyad Caliphate was built upon the legacy of the slave trade during the preceeding Rashidun Caliphate. This was built upon a combination of the enslavement of war captives during the Early Muslim conquests of the Caliphate; tributary and taxation slaves, as well as commercial slave trade by slave merchants.

War captives[edit]

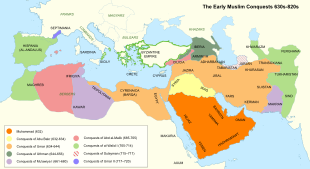

During the Umayyad Caliphate the Imperial Muslim conquests of the preceeding Rashidun Caliphate continued. The Empire of the Caliphate expanded to North Africa, Hispania and South France in the West, and the Central Asia and India in the East. The military expansion of the Empire took place in parallell with a slave trade with war captives, which expanded in parallell with the conquests, when captives of subjugated non-Muslim peoples were enslaved.

During the Muslim conquest of Transoxiana against Queen of Bukhara in Central Asia in the 670s, 80 Turkish war captives where taken by the Umayyad army, who broke their promise to return them and instead deported them to slavery in Arabia, where they rebelled and killed their enslaver, after which they comitted sucide.[1]

Warfare and tax revenue policies was the cause of enslavement of Indians for the Central Asian slave market, which started during the Umayyad conquest of Sindh of the 8th-century, when the armies of the Umayyad commander Muhammad bin Qasim enslaved tens of thousands of Indian civilians and well as soldiers.[2] The slave trade of non-Muslim Indians trafficked to the Islamic world via the Hindu Kush and the slave markets of Central Asia, such as the Bukhara slave trade, started during the Umayyad period, and was to go on for a thousand years.[2] During the Umayyad conquest of Sindh in the 710s the widow of the defeated Hindu king were, according to the traditional description, taken as a slave by the Umayyad commander, and her daughter Surya Devi were taken as war booty and given as a concubine to the Caliph in Damascus.[3]

After the rebellion of Governor Munuza of Cerdanya in the 730s, his Christian widow Lampegia were sent by the victorious Umayyad commander as a gift to the Caliph in Damascus.[4]

Tributary slaves[edit]

Slaves were also provided via human tribute and taxation. A permanent supply source of African slaves were provided to the Caliphate via the baqt treaty, which had been made between the Rashidun Caliphate and the Sudanese Christian Kingdom of Dongola in 650, and by which the Christian Kingdom was obliged to provide up 400 slaves annually to the Caliphate via Egypt.[5]

Slave market[edit]

The expansion of the Islamic Empire during the Umayyad Caliphate included larger areas of urbanised land than the previous conquests. The governing elite of the Caliphate came to estalish a permanent residence in an urbanised enviromnent, abandoning the traditional nomad bedouin life style. The urbanisation of the ruling elite resulted in a more sophisticated court life and state apparatus, which created an expansion of the institution of slavery. However, the slave trade and slavery built on the preceeding Rashidun Caliphate and mainly changed by expanson rather than by character.

Female slaves[edit]

Female slaves could be divided in to several categories: jariya or jawari (also called ama and khadima), who were working as domestic servants and could be used sexually by both their enslaver as well as other men; mahziyya, which was a concubine used exlusively for sexual slavery by only her enslaver and could be sold for thousands of dirham; um walad, a concubine who had given birth to a child acknowledged by her enslaver as his, who could no longer be sold and would become free upon the death of her enslaver; and a qina or qiyan, which was a female slave educated as an entertainer in singing, music, poetry, dance and recitation, and became a very expensive category of female slaves.[6]

In the late 7th-century the Umayyad dynasty settled in Damascus, where they established a major Palace complex and developed a sophisticated court life and state apparatus in parallell with their permanent urban settlement in a capital. The Caliphate also became a monarchy with an inherited succession. The harem institution of gender segregation and enslaved concubines were not a new institution, but the permanent urban settlement made it possible with a more efficient gender segregation and a larger number of slaves.

Women and girls from defeated non-Muslim peoples were divided as war booty in lager numbers, and subjected to a larger degree of segregation. Certain Umayyad military commanders could recived up to 500 concubines during the Imperial campaigns.[7] Ibn Sa'd estimated that up to a third of the sons of the Umayyad noblemen were the sons of enslaved women.[8]

Male slaves[edit]

While female slaves were more prioritized in the Caliphate than male slaves, the institution of military slavery expanded during the Umayyad Caliphate. The use of eunuchs also expanded in parallell with the expansion of the harem segregation of women.

During the Early Muslim conquests of the 7th- and 8th-centuries, a system of military slavery grew in which non-Muslim men from the conquered peoples such as Berbs and Persians were captured, enslaved, converted to Islam, manumitted and then enlisted in the Caliphate army, a custom which blurred the lines between free recruits and slave soldiers.[9] During the big Imperial conquests of the Umayyad Caliphate, slave soldiers grew to signficant numbers in the Caliphal army and played an increasingly important role.[10] The institution of military slavery developed during the Umayyad Caliphate was to become the dominant

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Naršaḵī, pp. 54, 56-57, tr. pp. 40-41; cf. H. A. R. Gibb, The Arab Conquests in Central Asia, London, 1923, pp. 19-20

- ^ a b Levi, Scott C. “Hindus beyond the Hindu Kush: Indians in the Central Asian Slave Trade.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, vol. 12, no. 3, 2002, pp. 277–88. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25188289. Accessed 15 Apr. 2024.

- ^ End of ‘Imad-ud-Din Muhammad ibn Qasim. The Arab Conqueror of Sind by S.M. Jaffar - Quarterly Islamic Culture, Hyderabad Deccan, Vol.19 Jan 1945

- ^ Philippe Sénac Les Carolingiens et al-Andalus : viiie – ixe siècles, Maisonneuve & Larose, 2002 (ISBN 978-2-7068-1659-8), réédition Folio 2014.

- ^ Manning, P. (1990). Slavery and African life: occidental, oriental, and African slave trades. Storbritannien: Cambridge University Press. p. 28-29

- ^ Taef El-Azhari, E. (2019). Queens, Eunuchs and Concubines in Islamic History, 661-1257. Storbritannien: Edinburgh University Press. p. 57-75

- ^ Taef El-Azhari, E. (2019). Queens, Eunuchs and Concubines in Islamic History, 661-1257. Storbritannien: Edinburgh University Press. p. 57-75

- ^ Urban, E. (2020). Conquered Populations in Early Islam: Non-Arabs, Slaves and the Sons of Slave Mothers. Storbritannien: Edinburgh University Press. p. 131

- ^ Lewis, B. (1990). Race and Slavery in the Middle East: An Historical Enquiry. Storbritannien: Oxford University Press. p. 62-63

- ^ Pipes, D. (1981). Slave Soldiers and Islam: The Genesis of a Military System. Storbritannien: Yale University Press. s. 122

Referenced material[edit]

- Segal, Ronald (2001). Islam's Black Slaves: The Other Black Diaspora. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 9780374527976.