Nikolai Pinegin

Nikolai Vasilyevich Pinegin | |

|---|---|

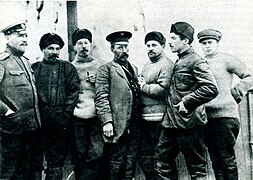

Photograph taken in 1905 | |

| Native name | Николай Васильевич Пинегин |

| Born | 27 April 1883 Yelabuga, Russian Empire |

| Died | 18 October 1940 (aged 57) Leningrad, Soviet Union |

| Occupation |

|

| Children |

|

Nikolai Vasilyevich Pinegin (April 27 (May 10), 1883, Yelabuga, Yelabuzhsky Uyezd, Vyatka Governorate, Russian Empire – October 18, 1940, Leningrad, RSFSR, USSR) was a Russian and Soviet writer, artist, Arctic explorer. He was a member of the expedition of G. Y. Sedov on the ship "St. Martyr Foka".[1]

He was born in the family of a provincial veterinarian. He began his education in the Vyatka real school, continued it in the Perm gymnasium, from which he was expelled. Nikolai Pinegin began to earn his own living at the age of 17. He entered the Kazan Art School, and in 1907, passed the exams to the Academy of Arts, but could graduate only in 1916. In 1909, he made his first trip to the Murmansk coast of the Kola Peninsula. In 1910, he took part in a trip to the northern tip of Novaya Zemlya, where he met G. Y. Sedov; in the same year he exhibited his paintings at the Academic Exhibition in St. Petersburg. In 1912–1914, he took part in the expedition of G. Sedov as an artist, photographer and cameraman. Sedov. On the basis of the materials collected during the expedition he made the first Russian film on Arctic themes and a number of paintings and sketches. Since 1916, he was an artist of the Black Sea Fleet, headed an art studio in Simferopol.

In 1920 he emigrated to Constantinople. From there he went to Prague and Berlin, where he worked as a theater artist and illustrator. In 1922, in Berlin, with the support of M. Gorky, he published his expedition diaries under the title "In the Icy Vastness". In 1923 he returned to the USSR and in the following year he took part in the Northern Hydrographic Expedition, making surveying flights together with B.G. Chukhnovsky. In 1927–1930 he led the expedition of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR to Big Lyakhovsky Island, where he wintered in the polar station established at Cape Shalaurov. Due to the failure of the expedition ship to Yakutia, the polar explorers had to return to the Arctic winter on their own. After his return, N. Pinegin worked at the Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute, where he founded the Arctic and Antarctic Museum and served on the editorial board of the Bulletin of the Arctic Institute. In 1932 he led an expedition on the icebreaker "Malygin" to Rudolf Island. In 1935 he was arrested, "as a former White Guard" was sentenced to five years of exile in Kazakhstan, but in the same year after the intervention of K. Fedin and V. Wiese was released, although he was not released. Wiese was released, although he was not rehabilitated. Due to the impossibility of working in academic structures, he returned to artistic and literary work. He died after a long illness, not having had time to finish the documentary novel "Georgy Sedov". Nikolai Pinegin is buried in the Volkovo Lutheran cemetery, his body was transferred to the Literary Bridges in 1950. A number of geographical objects bear the name of N. V. Pinegin.

Formation. First travels (1883–1910)[edit]

Early years[edit]

The origin of the Yelabuga Pinegin family is unknown, the surname is not recorded in the district. Family legend says that they were related to the merchant family of Shishkins, from which the famous painter came. This explains to some extent the artistic aspirations of Nikolai. He was born on May 10 (New Style), 1883 in the family of a traveling veterinarian Vasily Pinegin and his wife Matryona Feodorovna. The family had three children. Vasily was widowed in 1893 and soon married a second time. This marriage produced four girls. Nikolai says that he never got close to his stepmother and that the memories of his father and childhood were unpleasant.[2]

Nikolai Pinegin studied at the provincial real school for some time. Then the family moved to Perm, and the boy was sent to the local gymnasium. Nikolai studied badly, and his character made itself known: he was expelled from the fifth grade "for disobedience" (refusal to attend church services). Finally, in 1900, Nikolai left his family for good and began an independent life. To get to Kazan, he earned money by painting portraits, played in a brass band (he was generally characterized by musicality and had great abilities), joined a traveling troupe. In 1901, he was admitted to the Kazan Art School as a free student without examinations. Pinegin's petition of February 27, 1902 for admission to the ranks of active students of the IV class and exemption from examinations in arithmetic and geography due to the existence of a certificate of completion of four classes of the gymnasium has been preserved. The petition was granted, and from the same document it is known that in terms of social stratification he was "the son of a civil servant", and his father lived at that time in Nozhyovka, Perm Governorate. Pinegin was also mentioned in the "General Alphabetical List" of the Art School for the academic year 1904–1905; at that time he lived in the house of Petrova at 1st Soldatskaya Street.[3][4][5]

Travels in 1904–1909. First publications[edit]

The origin of N. Pinegin's polar aspirations was rooted in the Nordomania common in Russian culture at the turn of the century and the popularity of Knut Hamsun's works.[6][7] In his notebooks Nikolai mentioned that he was a good hunter and had wilderness survival skills. While still a student in Kazan he introduced a regime of austerity to save money for an artistic journey to the North. His plans were supported by his comrades: Semyonov, a student of natural science; Marosin, a topographer; and Kachalov, a wanderer who planned a trip for the summer of 1904. Semyonov suggested applying to the IRGS and wrote a letter to its chairman, Grand Duke Nicholas Mikhailovich. The letter outlined a plan for surveying the Northern Catherine Canal, for which the young men requested maps, geodetic instruments and 50 rubles for equipment.[8][9] In the reply the grant was refused ("for lack of information about the abilities of the persons you indicate to carry out the intended research"), but the expedition was accepted under the auspices of the Geographical Society and received an official letter obliging the local authorities to support the young people. The money saved was used to buy supplies. A tent was borrowed from an acquainted surveyor. The comrades reached Usolye, where they bought a boat for three rubles from a local resident, on which they continued their journey. The boat was usually pulled by string. The young traveler wrote the following about his impressions:

After the mouth of the Kolva River, where we immediately reached very sparsely populated areas, we were left to our own devices. The time for dreaming of adventures and heroic deeds was over, and it was time for simple everyday work. Every day, we would conscientiously pull a heavily loaded boat for twelve hours, climb into the water to pull the boat out of countless shallows, wade through waist-deep rivers and streams, and, surrounded by clouds of mosquitoes and gnats, try to make photographs and sketches. <...> All the game we had counted on had disappeared. We walked from morning to night, wet to the skin, cold and gloomy. We made fires at rest stops and tried to dry ourselves. And we grimly munched on tyurya made of breadcrumbs, topped with bits of butter.[10]

The journey (which was pretentiously called the "Volga-Dvinsk Expedition") ended in tragedy. At first, in the village of Kanavnaya, the locals thought the young men were carrying gold: here an official letter came in handy. The next day, while packing cartridges, Pinegin injured his hand (one of his fingers was permanently disfigured) when gunpowder exploded on the filling machine. He was sent by steamer to Cherdyn and had to be treated by his relatives in Perm. Semenov decided to return with him; two days after their departure, Marosin was mortally wounded by his own double-barreled shotgun, which he had slung over his shoulder. Kachalov was suspected of his murder, and only after much delay was he allowed to return home. Pinegin did not cool to the North, but came to the conclusion that it was necessary to increase his own knowledge and prepare thoroughly for campaigns.[4][11][12][13]

Pinegin's first two years back were financially difficult. To earn money, he managed to get a job as a draftsman for the Chinese Eastern Railway in 1906, and in 1907 he moved to the Saratov Artel as a surveyor. He continued to draw intensively and continued his studies at the Imperial Academy of Arts.[14][4] In the summer of 1909, Pinegin visited his relatives in Arkhangelsk. Here he joined the newly founded Society for the Study of the Russian North; the chairman, A. Shidlovsky, wrote the young artist letters of recommendation, an open sheet for boats, and provided free transportation to Murman. Nikolai Vasilievich sailed along the White Sea and the Kola coast on the steamer "Nikolai", which was specially designed for official trips, made many sketches and wrote a detailed report.[15] In addition, in 1909 and 1910 two essays were published in "Izvestiya Arkhangelskogo Society for the Study of the Russian North": "Ainovy Islands" and "From the Tales of the Lapland North". After the publication in the magazine "Sun of Russia" essay "In the Land of the Midnight Sun" in 1910 Nikolai Pinegin received a fee of 100 rubles and, having joined them savings in amount of 20 rubles, went on another trip.[16][17]

Journey to Novaya Zemlya[edit]

At the beginning of 1910, Pinegin was a student of the Battle Class of the Academy of Arts. He worked under the guidance of Professor N. S. Samokish.[18] In the summer of 1910, having found the funds, the artist took the first flight of the Arkhangelsk-Murmansk fast steamship to the Severny Island of Novaya Zemlya. On the steamer "St. Olga" (according to another version, "Grand Duchess Olga Konstantinovna") in that season sent carpenters to build a base in the Cross Bay and hydrographers to describe the same bay. The team of the Main Hydrographic Administration was led by the lieutenant of the fleet Georgy Yakovlevich Sedov, who left for the expedition two days after his own wedding. On July 21, the scientists and Nikolay Pinegin, who joined them, settled on the shore in a board barrack. He was to live in such conditions for three months. It immediately became clear that survival in the Arctic requires special caution: the steamship "Nikolai", which arrived on the 31st, brought the news that Maslennikov's fishing camp in Melkoy Bay had been completely wiped out. Then Nikolai Vasilievich, at the invitation of the commander of the messenger ship of the Northern Ocean flotilla "Bakan", made a "walk" to Cape Zhelaniya. On the way, in the South Sulmeneva Bay Pinegin for the first time saw a glacier flowing into the sea and witnessed the formation of an iceberg. With the permission of the commander, the officers of the "Bakan" shot the newly formed iceberg from a cannon. On Small Hare Island, the crew encountered Norwegian poachers, who fled and threw the prepared lard and skins ashore, which were brought on board, sealed and described by the revision committee. It was at Cape Zhelaniya that Pinegin first observed the "ice sky" — the reflection of solid fields of drift ice on a low cloud.[19][20]

Returning to Krestovaya Bay on August 18, Pinegin faced starvation: he himself had exceeded the meager budget, the carpentry crew ashore was running out of food, and scurvy was setting in. Nikolai turned for help to Lieutenant Sedov, whose party was seven versts to the west. This was the beginning of their friendship, which determined Nikolay Pinegin's life and profession. It was not until the end of September that the steamship "Saint Olga" arrived with supplies and fuel for the winterers, and Pinegin and Sedov returned to Arkhangelsk on board. Pinegin was once again convinced that he was suitable for the profession of polar explorer, that he had the necessary endurance, speed of decision-making and ability to navigate the terrain. He had time to paint: the sketches of Novozemelsk were exhibited at the Academic Exhibition in St. Petersburg. The artist was noticed, and one of the sketches —"Snow in Vera Bay"— was reproduced in the popular magazine "Niva" (№ 21 for 1911). By that time Nikolai Vasilievich was married, had three children, and his income was always insufficient. In the summer of 1911 he again went to the CER as a geodesist and was engaged in levelling the railway track between Harbin and Manzhouli station.[21][20]

Sedov Expedition to the North Pole (1912–1914)[edit]

The first wintering[edit]

After his return from Novaya Zemlya, Pinegin was in contact with G.Y. Sedov, visited him at his apartment, and discussed plans for an expedition to the North Pole. Nikolai Vasilyevich was the first to be invited to participate in the future enterprise, and when he left for Arkhangelsk in May 1912 to earn money and sketches, he was quite sure that the expedition would not take place. In Arkhangelsk, the artist met the geologist V. Rusanov, who dissuaded him from working with Sedov and offered him a place in his expedition to Svalbard. But Sedov's telegram, which Pinegin urgently sent to St. Petersburg to buy the missing equipment, decided everything: Pinegin was sent to St. Petersburg. because of A. S. Suvorin's agreement to the sponsorship of the project.[22][23] The expedition was equipped in a state of extreme confusion, the Maritime Ministry cancelled the radio operator's tariff, and Sedov's hard-won radio telegraph had to be left ashore. On August 19 (New Style), 1912 it turned out that the expedition ship "Saint Martyr Foka" was overloaded and the port authorities did not let it leave Arkhangelsk. G. Sedov ordered to throw away some provisions and equipment, including primus stoves. However, a film camera was left, which was to be handled by Pinegin. On August 24, the captain, his assistant, the navigator, the mechanic with an assistant and the boatswain of the "Foki" were dismissed, after which a new crew had to be hired as soon as possible. According to Pinegin's list, the crew consisted of 22 men.[24][25]

The expedition left the pier at three in the afternoon on August 27, 1912, and after refueling at the mouth of the Northern Dvina, the "Svyatoy Foka" headed north, having a reserve of coal for 23–25 days of travel.[27] Due to heavy storms, Sedov decided to enter Krestovaya Bay, where found an astronomical sign: it was to check the course of the ship's chronometers.[28] After anchoring on September 9–12, the expedition moved to the ice fields. On September 28, the old ship was obscured by ice, which meant a forced wintering. The unnamed bay of the Pankratieff Peninsula became the base. The situation with provisions was not so bad (the stocks were taken for three years), but there were only 25 tons of coal left, and it was compensated by the abundance of driftwood — trunks of Siberian wood taken from the sea. The expeditioners had both Russian winter clothing and Nenets fur clothing, as well as Eskimo suits. The upper deck was covered with earth and planks to insulate the living quarters; the hatches were padded with felt. Officers and scientists had cabins for sleeping and working. They were finally settled by October 2. Pinegin was appointed assistant meteorologist in addition to his artistic and cinematographic duties.[29][30] Some curios events took place. On October 30, Pinegin wrote in his diary:

I was working not far from the ship. Not wanting to lay down my arms, I made a sketch of a Siberian dog. I had not worked for more than half an hour when my hands began to stiffen. I went to the ship to warm up a bit. I returned about ten minutes later. As I approached the sketch box left on the snow, I noticed that a dog from the unnamed Arkhangelsk promptly ran away from the box. I approached confused, what was the dog doing there? Damn it, what's wrong with my work! Where are the paints from the palette? The dog licked it clean and the almost finished sketch was eaten for breakfast by a hungry dog! Should I laugh or be disappointed? Who would have thought that oil-soaked paints could be considered edible, even for a ever-hungry dog?[31]

The artist's notes about December are pessimistic. He admitted that the depression of the polar night was exactly as described by the participants of previous polar expeditions. January and February were marked by severe frost to −50°C, such temperatures were not expected for Novaya Zemlya. Dawn appeared on February 9, 1913, and the first sunlight was seen on February 18.[32] On March 18, Sedov and Pinegin spent six days surveying the Southern Cross Islands west of the hibernation site. They were convinced that there was a Pomors settlement on the newly discovered Pinegin Island. Due to ice conditions it was impossible to go further. The wintering showed that most of the sled dogs were not suitable for the needs of the expedition. When the weather warmed up, Pinegin and sailor Linnik surveyed the seaward side of the islands of Pankratiev, Nazimov, Bolshoy Zayachie and others between May 5 and 18.[33] At the base, the most arduous were the scientific observations, which were made every two hours, and taking readings from the instruments took about a quarter of an hour. They had to work both indoors and outdoors, recording the height of the tides, the shape and direction of clouds, the auroras, precipitation.[34] The extremely difficult psychological situation of the expedition also contributed to pessimism. Class conflicts played an important role, as officers and scientists treated the lower ranks of the crew with contempt, and sailors periodically refused to carry out what they considered to be unjust orders from their superiors. In the presence of Sedov and his authority, conflicts were of a sluggish nature and flared up in his absence. In Novaya Zemlya, during the absence of the commander, Captain N. Zakharov forbade the worship in the wardroom, claiming that he had not obtained permission. Doctor P. Kushakov was sent by Sedov to survey Krestovoy Island without having the necessary skills. The results of his work provoked mocking comments, in particular Pinegin depicted him in a caricature "looking at the stars and orders in the sky with a sextant placed in a backpack". Kushakov immediately challenged the artist to a duel, and G. Sedov had to threaten to send one of them home accompanied by a sailor.[35]

In the middle of the summer of 1913, the Foka was still not free of ice. The situation on board was almost unbearable due to the conflict between the expedition's chief, Sedov, and the ship's captain, Zakharov. On July 3, Captain Zakharov, carpenter M. Karzin, and scurvy patients (assistant mechanic M. Zander, V. Katarin, and Y. Tomissar) went to Krestovaya Bay to deliver mail to Arkhangelsk. Sedov asked the expedition committee to send a ship with coal, supplies and additional sled dogs to Franz Josef Land. For unknown reasons, Zakharov's team did not go to Krestovaya Bay, but travelled 450 km to Matochkin Strait and returned to Russia by ship. Pinegin erroneously wrote in his report that Zander died of scurvy (in fact, he lived in Latvia until 1941). Due to the late arrival of Zakharov's group, Sedov's request remained unanswered, which put the expedition in an extremely difficult situation. While waiting, Pinegin actively filmed the surroundings of the winter hut, and on August 24 he managed to record a bear hunting a seal. After that, the bear itself became the prey of Pinegin's dogs. These materials, not included in the film about the expedition, were rediscovered in Leningrad in November 1937.[36] During the hibernation G. Sedov managed to make a topographic survey of the entire northern coast of the northern island of Novaya Zemlya. However, the long winter interrupted the political plan – to reach the Pole by the Romanov Tercentenary.[37]

The second wintering[edit]

By the end of August 1913, due to the rainy weather, the ice was corroded and it was possible to try to start moving to Franz Josef Land. However, the ice fields did not open until September 3. At eight o'clock in the evening "Foka", unofficially named in his honor, left the port. Arriving at Cape Flora (September 13), the coal supply was almost exhausted. The crew counted on the coal store built for the campaign of "Yermak" Admiral Makarov in 1899, but it turned out that these supplies were used by the American expedition Fiala. Pinegin went ashore with a movie camera to film walruses and suggested using their blubber as a substitute for coal. Wintering on Northbrook Island was considered unpromising.[38] On September 18, the Foka encountered solid ice fields. On September 19, the second wintering on Hooker Island began. Since there was no ice compression in the chosen bay, the chief named it "Tikhaya" (quiet). There was a remarkable ice dome here that reminded Pinegin of the painting "Rest" by Čiurlionis and the cape in the newly discovered bay was named in honor of the artist.[39]

On board were no more than 300 kilograms of coal chips, some walrus blubber, and empty boxes and barrels suitable for use in the stove. One of the reasons for the lack of fuel was that during Sedov's absence in the previous winter, the officers burned coal in the stoves of their cabins, creating "unbearable heat" (about 25–30 °C). About 400 poods of coal were burned. Many representatives of the command staff asked the commander to return to Arkhangelsk. Navigator Sakharov and doctor Kushakov got into a fight, then Kushakov hit sailor Linnik, which angered the crew.[40]

At the beginning of the winter, Pinegin, returning from a solo excursion to Scott Kelty Island, fell under the ice two kilometers from the ship (air temperature −17 °C, water temperature −1.8 °C), but managed to get out. There were no consequences, not even a runny nose. On November 13, however, Pinegin's diary notes the onset of a scurvy epidemic on board. This was the result of an improper selection of provisions. By November 22, the scullery and the cook were affected, and on December 25, Sedov fell victim to the disease. The celebration of the New Year 1914 was gloomy: Pinegin noted in his diary that there were only seven healthy people on board, including himself, scientist Wiese, and sailors Pustoshny and Linnik. In January, the normal temperature overboard was −36°C, while in the living quarters it dropped to −6°C at night, and only the wardroom was kept at five degrees above zero. The orlop deck was abolished and the sailors lived together with the officers. On January 13, Pinegin sailed in stormy weather with a wind of 16 m/s.[41][42]

The plan of the sick Sedov to reach the North Pole was characterized by Pinegin in his diary in the following way:

Sedov's attempt is insane. To run almost 2000 kilometers in five and a half months without any stops, with provisions designed for five months for men and two and a half for dogs? However, if Sedov had been as healthy as he was last year with such outstanding young men as Linnik and Pustoshny, with proven dogs, he could have reached a great distance. Sedov is a fanatic of achievement, perseverance incomparable.[43]

With the commander, no pleading worked. After having argued with Pinegin, he said: "All this is true, but I believe in my destiny".[44][45] It was not possible to send a relief party with supplies: there were no healthy sailors left. Doctor Kushakov (a veterinarian by training) assured Sedov that the swelling of the legs was not caused by scurvy, but by rheumatism. On February 13, the commander asked Pinegin to take a photo of him: it was the last photo of G.Y. Sedov. On February 15, the sick chief together with Pustoshny and Linnik went north with 20 dogs on three sleds. They were accompanied by Wiese and Pinegin to the Cape Markema. On March 18, exhausted sailors returned to the ship and reported Sedov's death, which occurred on March 5, 1914. They often got lost and could not even explain where they had buried Georgy Yakovlevich's body. On March 25, Pinegin and Inyutin, a carpenter, on the orders of the deceased commander, set out for Cape Flora. It took them two days to cross from Tikhoy Bay. Nikolai Vasilyevich visited the "Eira's House", left by Leigh Smith's expedition. Then Pinegin and Inyutin tidied up one of the huts on the cape and tried to find the necessary supplies for their comrades, including tobacco. By the time they returned, most of the crew had been cured of scurvy thanks to bear hunting.[46][47]

Returning[edit]

The topmasts and bulwarks were removed and sawed for fuel by mid-July. The results of the scientific work were sealed in zinc boxes in case they had to abandon the ship and go by a launch.[48] After Sedov's death, second mate Nikolai Sakharov took command, and V. Wiese and N. Pinegin became his deputies. In mid-July, the crew was sent out to saw ice, and the storm that broke on the 25th broke the pack ice. The anchor was hoisted at ten o'clock in the morning on July 30. It was decided to sail north, but almost immediately the ship ran aground near Scott Kelty Island. To unload as much as possible, 35 tons of fresh water was drained and a two-ton anchor with chain was thrown out. Soon the ice field pulled the ship into the water. Near Cape Flora, Pinegin worked as a navigator because he knew these places. During this time, three walruses and two seals were taken, the fat of which supplemented the wood in the boiler furnace.[49][50] On August 2, off Cape Flora, the crew noticed people approaching in a kayak to board the ship. It was the navigator of the Brusilov expedition, V. Albanov, who, together with the sailor Konrad, had left his expedition and was moving to Northbrook. The other members of his sledge party perished or disappeared without a trace.[51]

On August 8, the crew of the "St. Foka", after having dismantled the shore buildings for fuel, set out in search of the men of Albanoff's party. They rounded Bell and Mabel Islands, visited Eira Harbor, blew whistles and fired signal cannons. Finding no one at Cape Grant (Albanoff assumed at least four must have survived), it was decided to head south. Albanov kept a copy of the Brusilov expedition's log and meteorological data up to the time the schooner St. Anna was abandoned. Albanov's travel diaries were published by Pinegin in 1926 with his own preface.[52] On August 10, the fuel ran out, and soon the "St. Foka" was pinned down by ice fields. The drift continued for 9 days, and when the wide channel opened on August 26, the crew began dismantling all superstructures and internal bulkheads to maintain steam pressure. Then it was the turn of the beams, which were broken one by one. After leaving the ice, the expedition could continue. On August 30, 1914, the "St. Foka" arrived at the Rynda camp on the Kola coast. It turned out that a search expedition had been sent to find Sedov, Brusilov and Rusanov. The survivors of the expedition reached Arkhangelsk on the steamship "Emperor Nicholas II" at the expense of its captain, since no one had money; "Foka" was also towed to Arkhangelsk.[53]

War, emigration and re-emigration (1914–1923)[edit]

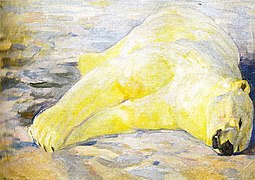

After returning to Petrograd in the fall of 1914, Pinegin found himself in the spotlight as the first Russian artist to participate in a polar expedition. He was able to return to the Academy of Arts and presented a series of 58 of his sketches at the "Spring Exhibition" in 1915. The "Spring Exhibitions" had been held since 1897 on the initiative of A. I. Kuindzhi, especially for graduates of the Academy who were not members of creative societies. For his sketch "Polar Rest" Nikolai Vasilyevich was awarded the Kuindzhi Prize of the first degree, several of his works were bought by museums and private individuals.[54][55][4] In 1916, Pinegin finished his studies at the Academy of Arts, but due to war circumstances he did not make his diploma painting and was accepted as an art historian at the Historical Unit of the Imperial Black Sea Fleet in Sevastopol. He received a long leave of absence to participate in the Spring Exhibition of 1917 (presenting 13 of his works), which lasted from February 12 to March 26, thus becoming an active witness of the February Revolution. Because of his fame, Nikolai Vasilievich was even elected to the Council of Workers', Peasants' and Soldiers' Deputies (from the Academy of Arts), but he preferred to return to the Crimea.[56] At the invitation of S. Makovsky, Pinegin headed an art studio in Simferopol. In October 1918 he participated in the exhibition "Art in the Crimea" together with S. Sorin, S. Sudeikin and the Milioti brothers. Due to the civil war, the studio in Simferopol was dissolved; Soviet historiography blamed Denikin's government. Pinegin returned to Sevastopol, where he lived in Sobornaya Street. In 1919 Nikolai Vasilyevich met the journalist George Grebenshchikov, who published an article about the artist's personality and lectures in Our Newspaper on March 30, 1919.[57] Pinegin painted a portrait of Grebenshchikov, and together they appealed to P. Struve (head of foreign policy in Wrangel's government) to go to Europe with their families. Struve replied: in September 1920 he sent a telegram to the Ambassador of the Provisional Government in Paris V. A. Maklakov about the issue of visas. Grebenshchikov and his wife left for Istanbul on September 18, 1920 (New Style), while Pinegin stayed behind because of the need to formalize the exported paintings and slides.[58][59]

Arriving in Istanbul in October 1920, Pinegin expected to go immediately to Paris, the capital of Russian emigration, but in fact he stayed for a long time. He had to work as a porter, painting signs, giving tours of Byzantine monuments. At that time he met I. S. Sokolov-Mikitov. In his characteristic way, Pinegin depicted the history of their communication in the form of a complex scheme, including three stages – in the Crimea, in Constantinople and further in Europe. In the hungry winter of 1919 in Sevastopol, the homeless Sokolov-Mikitov became interested in Pinegin's paintings exhibited in the Naval Archive, met the artist, and then got a job as a sailor. The acquaintance ended dramatically: when the steamer on which Sokolov served was loaded with coal, the sailor recognized Pinegin in one of the loaders. To help him then he was powerless.[60] It wasn't until 1921 that Nikolai Vasilievich managed to get a visa. However, the artist preferred to go to Prague. Already in the city he learned about the March publication of G. Grebenshchikov in the Paris newspaper "Obschee delo" ("Common Cause"), dedicated to his own judge. Grebenshchikov in the Paris newspaper "Common Cause", dedicated to his own fate. Thanks to the help of acquaintances, Pinegin received an order from the National Theatre to create sets for the production of the opera "Boris Godunov". However, this did not improve the emigrant's extremely difficult financial situation. Finally, in the spring of 1922, Nikolai Pinegin moved to Berlin and was mentioned in a letter from A. Remizov dated April 14.[61] One of the artist's drawings ended up in the album of S. P. Remizova-Dovgello. P. Remizova-Dovgello. Communication with Pinegin probably reminded Remizov of his plans in the 1910s to go to collect folklore material together with M. M. Prishvin. The motives of the northern folklore were used in the story "Glagolitsa", probably the coincidence of interests of the new acquaintances. In the newspaper "Days" (December 24, 1922) saw the light Pinegin's fairy tale called "Noida" from a long-standing collection of 1910. In addition, the artist cooperated with the publishing house of E. A. Gutnov, which published the magazine "Spolokhi" and the series "Spolokhi Library". Pinegin made illustrations for Remizov's short stories from the cycle "Red Poyogrunki", but due to market difficulties the publication was interrupted. However, due to the announcements that appeared in the press, this edition was later included in Pinegin's bibliography. Pinegin's illustrated edition of Remizov's "Tsar Maximilian" (published by Century of Culture) also failed.[62] As a result, the most successful Berlin project of Nikolai Vasilievich remained the illustration of the last book of the tetralogy "The Thinker" by Mark Aldanov — "Saint Helen, a Small Island", published in 1923 by the "Neva" publishing house.[63]

Pinegin was also associated with the Berlin "House of Arts", which opened in late 1921.[64] However, the his financial situation remained extremely difficult. In the summer of 1922, through Ivan Sokolov-Mikitov, he met Maxim Gorky, who was interested in the diaries of the Sedov expedition and offered to publish them. The result was the publication of the book "In the Icy Expanses", which was immediately noticed by literary critics and polar specialists. This book attracted the attention of Aleksei Tolstoy. The result was Pinegin's desire to return to the new old homeland – the Soviet Union. This became possible after an appeal to the People's Commissariat by the Berlin "Voice of Russia" reporter B. M. Shenfeld-Rossov about Nikolai Vasilyevich's non-involvement in the White movement. In 1923 he returned to Petrograd, and the following year Gosizdat published the first Russian edition of "In the Icy Vast". Pinegin was invited to continue his work about Arctic.[65][66]

In Soviet Union (1924—1940)[edit]

Expeditions in the first half of the 1920s[edit]

After returning to the USSR, Pinegin got a job in the Polar Commission of the Academy of Sciences, where a plan for further exploration of the North Land was developed. It was planned to send a sailing motor vessel in the summer of 1924, but for financial reasons the plan was not realized. Instead, Pinegin was sent to the Northern Hydrographic Expedition under the command of N. Yevgenov. The expedition on the ship "Azimut" had a seaplane "Junkers U-20" piloted by B. Chukhnovsky. The main goal of the expedition was to determine the possibilities of regular sea communication between European Russia and the basins of the Ob and the Yenisei. In addition, it was necessary to equip coastal weather stations and a number of other facilities. The expedition left Arkhangelsk on August 9, 1924 and reached Novaya Zemlya within five days. Due to constantly stormy weather, Chukhnovsky made his first flight only on August 21. The result of the first flights was the establishment of coincidence of the theoretical range of visibility with the physical one in the Arctic conditions. The flight with Pinegin-observer took place on August 25, the target was Mehrengina Island. It was also necessary to determine the spread of ice along the western coast of the South Island and visually identify shoals dangerous for navigation. Pinegin's qualification allowed to distinguish underwater and subglacial relief by color change of the sea surface or ice fields. Visibility under open water was up to 25 meters. Nikolai Vasilyevich was also engaged in aerial photography under extreme conditions: there was no film for the automatic Pate camera, and he had to work by leaning out of the cockpit. In Pinegin's own words, "every shot was a battle. We had to made a lot of croquis and make many shoots of topography from the air, in conditions where the wind pressure was ripping pencils out of our hands. In all, 12 flights totaling 13 hours were made during the Northern Hydrographic Expedition, and technical requirements for polar aviation were formulated.[67]

In 1925 N. V. Pinegin was a member of the committee for the development of an expedition to the land of Nicholas II (that was the name of Severnaya Zemlya at that time). On November 17, he submitted his own plan, according to which the sail-motor ship would winter off the coast of Taymyr and then go to Severnaya Zemlya by sleigh. For this purpose seven men and 30 sled dogs with supplies for one and a half years would be enough. The weak point of all the presented plans was the lack of a suitable polar ship, while the construction of a new one or its purchase abroad required funds that were not available. In 1926 Pinegin published in Gosizdat the diary of V. Albanov with his own preface. The edition of 7000 copies was quiet significant for that time and was the subject of the publication.[68][69]

Expedition to Bolshoy Lyakhovsky Island[edit]

In early 1927, the Commission for the Study of the Yakut ASSR of the USSR Academy of Sciences commissioned Pinegin to establish a stationary geophysical base on Bolshoy Lyakhovsky Island, which was to work in tandem with the geophysical laboratory in Yakutsk. A radio station operating on both long and short wavelengths was planned. The base was tentatively to be located at Cape Shalaurova, although the final choice of location was entirely within Pinegin's competence. The team included: geologist M. M. Yermolaev, hydrologist K. D. Tiran, geographer and biologist A. N. Smesov, radio operator V. V. Ivanyuk, and motorist V. I. Ushakov.[71]

To reach their destination, they had to travel about 24,000 kilometers along the Trans-Siberian Railway and through the deserted regions of Yakutia. The 55-ton schooner Polar Star (captained by Y. D. Chirikhin), transferred from Kolyma to the mouth of the Lena, was to serve as a supply ship.[72][73] Under Pinegin's command, the schooner reached Yakutsk, where it remained for repairs until the following year. On July 20, 1928, the crew sailed to Bolshoy Lyakhovsky Island with the barge Tyumenka in tow. After loading coal in Sangar-Khai and replenishing supplies in Zhigansk (including hay for four cows taken on the expedition), the "Polar Star" arrived in Bulun on July 31. In the fishing village of Bykov Cape they picked up the sled dogs Pinegin had personally selected the year before. On August 1, while visiting Tiksi, the crew entered solid ice fields. Until August 23, the schooner maneuvered in the ice passages, moving extremely slowly toward the destination. The stay on Bolshoy Lyakhovsky Island lasted from August 26 to September 1. After unloading Pinegin's group, the schooner hurried to leave. The team was left with the Norwegian motorboat "Mercury Vagin", built under the direction of O. Sverdrup. Within a week, the expedition's camps were covered with a thick layer of snow. The team managed to erect a prefabricated winter house and a barrack with a tar paper roof.[72][74] Regular observations began on October 21, and on November 26, the Presidium of the USSR Academy of Sciences noted Pinegin's achievement with a radiogram signed by Academy President S. F. Oldenburg.[75] On December 2, 1928, a meteorological weather balloon was launched and observed with a theodolite to an altitude of one and a half kilometers, after which it disappeared from sight. From then on, regular observations were made and the results sent by radio. In March 1929 the radio communication brought bad news: "Polar Star" did not return to Yakutsk and had to winter in the Neelov bay at the mouth of the Lena river, which was a guarantee that it could not make a summer voyage to the New Siberian Islands. The auxiliary ship Stavropol, sent from Vladivostok, also wintered at Cape Severny. This meant that the nine-man crew had to wait until December to return by ice and land. They also had to conserve supplies, as the size of the Polar Star did not allow them to carry more than a year's worth of food and fuel. From Leningrad it was recommended to leave only four people at the station, who could feed themselves by hunting, and to send the others by sleigh. The problem was that this would mean stopping scientific observations.[76]

Nikolai Vasilyevich Pinegin suggested sending two men and reducing the rations and rest time for the rest. From the 1st of April the rations were reduced, and the team remained on them until December. A little earlier, on March 30, 1929, the chief went 60 km to the Vankin camp, where he met with industrialists who sold furs from spring fishing. The final destination was the Kazachye camp at the mouth of the Yana River, where it was possible to get some flour and other supplies. Despite the thirty-degree frost, Pinegin's party traveled 80 to 90 kilometers a day. They reached their destination on April 11 and spent 17 days in the settlement, having bought on credit the necessary supplies and even 17 riding reindeer needed to deliver the materials received at the station. The return trip was made on April 28. Despite the strongest blizzards, the group made its way along the coast of Kotelny Island. They refined the map between Cape Medvezhy and the Balyktakh River.[77] Despite the additional supplies, they would run out by the twentieth of December; by November, the station was starving, and Pinegin likened his situation to that of a "besieged city" in his diary. The promised crew change did not happen: the rescue ship got stuck in the ice in early fall. Pinegin let three other members of the party go with the returning fur trappers and stayed with the carpenter V. Badeyev to wait for the replacements. Only in the night of December 19, 1929, the radio operator of the new party Andreev arrived with fresh supplies and mail, and the rest of the meteorological team arrived two days later. Acceptance of the cases and resumption of observations lasted until December 27, after which Pinegin and Badeev left for Yakutia by sleigh. They arrived in Kazachye on January 15, 1930. Then they had to go 1300 km to Verkhoyansk on the reindeer trail in fifty-degree frost; Pinegin decided to go this way alone on light dog sledges and left on January 23. On January 27 he encountered the end of the polar night. The hardest passage in extreme cold severely undermined the polar explorer's health and significantly shortened his life.[78]

On January 8, 1930, the Council of People's Commissars allocated 100,000 rubles for the work of the Lyakhovskaya Geophysical Station, noting the strategic importance of the outpost of Soviet science in the Arctic. The work of N. V. Pinegin and his successor N. N. Shpakovsky was recognized as exemplary.[79] Based on the expedition's materials, Pinegin published a popular book "In the Land of Arctic Foxes" and prepared a two-volume book "Polar Geophysical Station on Bolshoy Lyakhovsky Island". The scientific collection included three articles by Pinegin himself: a general review of the expedition's progress, "Materials for the Economic Survey of the Novosibirsk Islands", and the processing of meteorological observations during the sea crossing in 1927. The "Cloud Atlas" of the Main Geophysical Observatory was prepared on the basis of the observations collected by Pinegin.[80] The scientist himself lived in a communal apartment in the house No. 69 in Bolshaya Pushkarskaya Street in Leningrad.[81]

Nikolai Pinegin in the first half of the 1930s[edit]

The Arctic Museum's foundation[Note 1][edit]

In November 1930 a museum was established within the Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute, which was transformed into the All-Union Arctic Institute. It was founded by the director of the institute, R. L. Samoilovich, academician Y. M. Shokalsky, polar explorers V. Y. Wiese, Y. Y. Gakkel, and A. F. Laktionov. The purpose of the museum was "to demonstrate the achievements of Soviet scientists in the exploration of the Arctic, as well as to popularize scientific knowledge about the polar regions". The first director of the museum was N. V. Pinegin. In the first years the staff of the museum was small, its employees were engaged in purposeful collection of exhibits and development of the scientific concept of the exposition. The expeditions of the Institute were recommended to donate to the museum objects and documents related to the activities of Soviet polar explorers. However, until the mid-1930s the museum did not have a separate room.[82][83]

Journey to Franz Josef Land[edit]

In 1931 the company Intourist organized a tourist trip to Franz-Josef-Land to compete with the Norwegian Svalbard. The icebreaking steamship "Malygin", which had two first-class cabins on board, was chosen to transport the tourists.[84] Scientific research within the framework of the International Polar Year was also planned; Y. V. Wiese was appointed as the chief of the expedition, and N.V. Pinegin as his deputy. In the "Bulletin of the Arctic Institute of the USSR" (1931, 5, p. 82) it was stated that according to the initial plan the participants of the voyage would visit the Soviet polar station in Tikhaya Bay and other islands of historical or natural interest. Then it was planned to go to the northeastern part of the Kara Sea). The sensation, which should have increased the interest in the expedition, was the meeting of the ice-breaking steamer "Malygin" with the German airship "Graf Zeppelin", which was confirmed by R. L. Samoilovich, who took part in the flight together with E. T. Krenkel. The correspondent of "Izvestia" I.S. Sokolov-Mikitov, with whom Pinegin had been friends since his stay in the white Crimea in 1919–1920, was among those who reported on the "Malygin" campaign. The correspondents also included: the writer L. F. Mukhanov, the journalists P. F. Yudin and M. D. Romm, M. K. Rosenfeld. Among the tourists was Umberto Nobile, who was looking for traces of part of his team that had disappeared in 1928. Nobile willingly joined the scientific team, and Pinegin shared warm clothing (coat and brachyramphus feathers hat) with him. Also on board was Lincoln Ellsworth, who financed and participated in the flight across the Arctic to conquer the North Pole under the command of Nobile and Amundsen. Among the famous polar explorers on board was I. D. Papanin, the steamer was commanded by D. T. Chertkov. In total, there were 86 people on board the Malygin, including 44 crew members, 11 servants and 31 passengers, whose names were mostly not mentioned.[85][86]

The "Malygin" left Arkhangelsk on July 19, 1931, and in the evening of July 23 it reached Newton Island in the Franz Josef Land archipelago, where the first bear hunt was organized. Before that, the ship passed through a thin ice field more than 100 miles wide, which presented no difficulties. On the way to Cape Flora, the "Malygin" ran aground, but managed to free itself without damage. At least 125 icebergs of various sizes were grounded on the same shallow shore. On July 24, a 9-point storm broke out, which prevented us from landing at Cape Flora. On July 27 there was a meeting with the airship "Graf Zeppelin" in Tikhoi Bay. The participants of the meeting exchanged mail, but the Soviet side did not receive the data of aerial photography under the pretext that the films were exposed (according to I. Papanin, these data were received by the German military intelligence).[87] A polar bear hunt was organized to entertain the passengers. Landing at Cape Flora was not possible until July 31. In early August, they approached Jackson Island, where tried to find Nansen's winter camp, but without success. Then they went to Rudolf Island, but due to heavy fog from August 2 to 4, the "Malygin" drifted in fields of solid ice. Only on August 5th they reached the Teplitz Bay full of broken ice, where they found the camp of the Fiala expedition, from which various relics and equipment were taken for the Arctic Museum. On August 7, near the southwestern part of Karl-Alexander Island, the Pontremoli Ridge was discovered – three small islands named after the Italian scientist who died in the crash of the airship "Italy". It was impossible to enter the Strait of Austria, so "Malygin" moved to the British Channel to check the existence of Harmsworth Island. It turned out that instead of the two islands shown on Jackson's map, there was a single landmass covered with an ice dome and named Arthur. Ice conditions did not allow exploration of the north coast of Alexandra Land in search of the remains of the "Italy". On August 8, the crew visited Alger Island, where the hut of the 1901–1902 Baldwin expedition was found. The next day, the steamer set sail for the Barents Sea. As the coal was running out and the weather was very foggy, Captain D. Chertkov refused to call at Uyedineniya Island. On August 12, the passengers landed in Andromeda Bay on Novaya Zemlya, where a reindeer hunt was organized. A total of 11 bears and 6 reindeer were harvested during the trek.[88] On August 15, they visited the Polar Geophysical Observatory at Matochkin Strait, and on August 20, the "Malygin" returned safely to Arkhangelsk. According to V. Wiese, the temperature of the surface layer of the sea was measured at 295 points, water samples were taken for analysis of chlorine content at 273 points, and samples for pH determination were taken at 138 points. Meteorological observations were made every 4 hours.[89]

The Second International Polar Year[edit]

N. V. Pinegin's activities were closely connected with the Second International Polar Year (IPY) in the years 1932–1933. As part of them, Vasilyevich was appointed head of the expedition on the "Malygin", the main purpose of which was the landing of 29 polar explorers under the leadership of I. D. Papanin on Rudolf Island. This was one of nine new polar bases that the USSR was obliged to open as part of the International Polar Year.[90] Also on board were foreign tourists (including Vilhjalmur Stefansson)[91] and the Secretary General of the Aeroarctic Society Walter Bruns, who was to study the possibility of landing the airship on ice. The "Malygin" left Arkhangelsk on August 15, 1932, and arrived seven days later at Tikhaya Bay on Hooker Island without encountering any ice fields. After transferring cargoes for the existing polar base, the "Malygin" sailed on August 26 through the British Channel, which was almost ice-free. The weather began to deteriorate after August 29, storms began, which brought ice fields to Teplitsa Bay. They managed to unload all the supplies and equipment for the polar station, and on August 30, the steamer headed north for oceanographic work. Despite the presence of solid ice fields, it was possible to reach 82°29' N (setting a record for a polar ship) and measure the sea depth to 230 meters. The coal reserve did not allow reaching the ocean depths, so the expedition carried out hydrological work around Rudolf Island. After making sure the station construction was complete, Pinegin's team refueled the Tikhaya base and returned to the mainland. After two ten-point storms, the Malygin arrived in Murmansk on September 17. Despite the harsh weather conditions, 216 stations for determining the salinity and temperature of the surface layer of seawater, 66 stations for determining the alkaline reserve and 7 deep-water stations north of Rudolf Island were completed. A water layer with a temperature of +2 °C was detected north of 82°N at a depth of 100 m. During the stands, the intensity of cosmic radiation and ion lifetime, atmospheric dustiness were determined. The thickness of the ozone layer was also studied. N. V. Pinegin personally conducted a topographic survey of the ice-free land in Teplits Bay and near Cape Stolbovoy. Since it had been mapped during the expeditions of the Duke of Abruzzi and Ziegler-Fiala, it was possible to study the degree of glaciation of Rudolf Island over a 30-year period.[92][93] Based on the results of the voyage on the Malygin, N. V. Pinegin presented a number of scientific publications in the 34th volume of the Proceedings of the Arctic Institute, including in the field of deep-sea research. After his return he also took the post of editor of the Bulletin of the Arctic Institute.[93]

Exile. Last years of life[edit]

In 1932–1934 N. V. Pinegin was actively engaged in editorial and literary activity. In 1932 in Arkhangelsk he published an adaptation of the diary of V. Albanov under the title "70 Days of the Struggle for Life". In the same year in Leningrad the book about the expedition to Bolshoy Lyakhovsky Island "In the Land of Arctic Foxes" with illustrations by the author was published in 7300 copies. In 1934 Nikolai Vasilievich republished in Leningrad Albanov's diaries "Lost in the Ice" with the subtitle "The Polar Expedition of G. L. Brusilov".[94]

Since the early 1930s, Pinegin's relations with the party organization of the Arctic Institute had deteriorated badly. As a result, he was denounced to the NKVD department. After Kirov's assassination, the Leningrad intelligentsia was persecuted. Under the extrajudicial process of expulsion in March 1935 received and Nikolai Vasilyevich. In the indictment of the Special Council it was stated:[94]

In 1920. Pinegin, living in Sevastopol, with the help of Krivoshein, the minister of agriculture in Wrangel's government, obtained a passport and a visa to travel abroad. From Sevastopol Pinegin went to Constantinople, from where he went to Prague a year later, in 1921. From Prague he went to Berlin and at the end of 1923 he legally returned to the USSR. Pinegin, as a white emigrant, had correspondence with abroad until the end of 1934. On the basis of the above, I would like to expel N. V. Pinegin from the Leningrad region.[95]

Pinegin was sentenced to five years of exile in Kazakhstan, which he served in Shalkar. However, he had his defenders, including V. Wiese and the writer K. Fedin. They actively defended Nikolai Vasilyevich, pointing out his outstanding role in the development of the North. A few months later the case was reviewed and Pinegin returned to Leningrad. However, he could not be reinstated to his position at the institute.[96]

Pinegin was forced to dedicate himself to painting and literature. In 1936 Nikolai Vasilyevich and Nikolai Alekseevich Zabolotsky met in Gitovich's house and became interested in the polar explorer's stories about shamans. According to them, when an anti-religious propagandist came to the camp to demonstrate the radio, the chief shaman summoned his comrades with an incantation and then showed the "fighters against superstition" his power: he made the trees sway to the beat of the vedun. On the basis of this oral story Zabolotsky wrote the poem "Shaman", but in 1948 he considered it unsuccessful and burned the manuscript, the existence of which is known only from the oral testimony of the writer's entourage. It is impossible to separate Pinegin's plot from Zabolotsky's text.[97]

At the end of the 1930s, Pinegin was in contact with V. Kaverin, who described the furnishings of apartment 80 in house No. 9 on the bank of the Griboedov Canal as a "polar house". In the novel "The Two Captains" it is mentioned that during the training camp of the pilot Sani Grigoriev during the search expedition for him "P., an old artist, a friend and companion of Sedov, in his time... printed his memoirs". In his own brief recollections of his communication with Pinegin, Kaverin mentioned that he was treated to canned food from Cape Flora, picked up in 1914, "and to my amazement, they turned out to be excellent".[98] According to Ilya Brazhnin, Pinegin's personality turned out to be "the luckiest find" for Kaverin's novel: both as "a part of Sedov" and as "a rare receptacle of what Kaverin wanted and intended to write about". In 1939, I. Brazhnin accompanied Pinegin on his last trip to the polar region, in connection with the 20th anniversary of the liberation of Murmansk from the White Guards and foreign invaders. The result was the collection "Soviet Polar Region", which included articles by 14 Soviet writers, including Kola sketches by Pinegin himself.[99][100] After 1938, Nikolai Vasilievich began to write a large fictional-documentary book about Georgy Sedov, which was published in the 10th and 11th issues of "Zvezda" for 1940. The author himself, according to the memoirs of V. Wiese, called this text a "full-length portrait of Sedov", willingly shared his ideas and read the finished fragments aloud. During his work on the first part of the novel, the 57-year-old author died. His death was announced on the radio. His death was announced on the radio. In the 11th issue of "Zvezda" Kaverin placed an obituary "In memory of Pinegin". Another obituary was placed in the magazine "Literaturniy Sovremennik" V. Wiese; the writer's name on the title page of "Soviet Polar" was placed in the mourning frame. Pinegin's ashes were buried in the Volkov Lutheran Cemetery. After the war the grave was moved to Literats' Bridges (Geographers' Path) and in 1950 a new gravestone by N. Eismont was installed. In 1953 the full text of the documentary novel "Georgy Sedov" was published, which was finished according to Pinegin's drafts by his widow (E.M. Pinegina) and V. Wiese.[101][102][103][100][104][105]

Family and personal life[edit]

There is little information about the private life of N. V. Pinegin in the existing literature. His first wife (Alevtina Evlampievna) belonged to the "progressive" women, was "revolutionary liberated". They had three children: daughter Tatiana and sons Georgy (or Yuri, born in 1906) and Dasid (or Dasiy, born in 1909). During their father's expeditions, the children were sent to a boarding school. Later, Yuri-Georgy also became a polar explorer, working at the Arctic Institute.[107][108] Daughter Tatiana survived the Siege of Leningrad, was evacuated to Perm, where she was sheltered by the family of I. S. Sokolov-Mikitov, with whom Pinegin was very friendly.[109]

It is not known exactly when Nikolai Vasilievich and Alevtina Evlampievna separated. Pinegin and his second wife, Elena Matveevna (née Sevostyanova),[110] met during the Revolution at the art school where he was a teacher; they were eighteen years apart in age. She was the granddaughter of a St. Petersburg tailor who worked as a servant in the imperial palaces. In 1935 she went into exile in Kazakhstan, where she earned a living as a journalist; there they met again. From exile in Leningrad they returned together, Nikolai Vasilievich insisting that Elena continue her education at the Herzen Pedagogical Institute and become a museum expert. Herzen and became a museum guide. There were no children from this marriage.[111]

In Leningrad, thanks to the efforts of M. Gorky, Pinegin lived in the House of the Figures of Literature and Art (Griboedov Canal Embankment, No. 9, apartment 80). Judging by the memories of his relatives, Nikolai Vasilyevich did not like the bohemian way of life, almost never went to see guests, "sit-downs he did not like" (although there is at least one evidence that he knew and liked to hold spontaneous parties.[112] Among his neighbors in the house, he most often communicated with M. Zoshchenko and O. Bergholtz, as well as with V. Kaverin.[113] Elena Matveyevna Pinegina survived the blockade, in 1968 she published in the magazine "Star" an essay dedicated to her deceased husband.[114] Lev Loseff left a memoir judgment about his residence:

Among the northern writers there was also a writer and artist with a geographically appropriate surname, Pinegin, but he was already dead... Pinegin's widow, Elena Matveyevna, a beautiful middle-aged woman, was a friend of my mother's. <...> Pinegin's apartment was one floor above ours, and that's why it was brighter there. Also, half the floor in the study was covered with polar bear hide, and on the walls were Pinegin's paintings of bright blue skies and brilliant white ice (just like the Rockwell Kent paintings I saw much later) and all sorts of polar trophies. My mother was talking to Elena Matveyevna in another room, and I was invited to look at the polar curiosities. I touched a bear's head with a dog's glass eyes. A plate with sticky baleen. I looked at pictures, unfortunately not animated by a sailing ship or a steamboat – just ice, sky, water.[115]

Nikolai Pinegin: writer and artist[edit]

N. V. Pinegin's pictorial language[edit]

Nikolai Pinegin is considered to be one of the founders of the Russian Polar School of artists. Pinegin's brush belongs to such works as "Polar Bears", "Polar Landscape", "Glacier on Franz Josef Land", "Ice Crack", "Ice Floe", "Whitish Light", "Three-layer Fogs", "Cape Flora", "Waterfall on the Tuloma River, ", "Kildin Island", "Rubini Rock", "Taisia Glacier", "Ice Hills", "Iceberg", "Spring Symphony of the North", "Unrecognizable Bay", "The Rough Shores of Novaya Zemlya", "Matochkin Shar", and "Stamukha". During his expeditions he created a large gallery of graphics. Much of his heritage was destroyed during the Siege of Leningrad in 1941–1942. Some of his oil paintings are in the collections of the State Russian Museum and the Russian State Arctic and Antarctic Museum, but his name remains virtually unknown.[4] Two personal exhibitions were held posthumously in Leningrad: the first was opened on February 17, 1959 in the small exhibition hall of the Artists' Union, the second — on October 23, 1962 in the small hall of the Geographical Society.[116] In 2008 some works of N. Pinegin were reproduced in the book "Artists — participants of expeditions to the Far North" (ISBN 978-5-91519-007-7), in 2012 there was an exhibition "History of exploration of the European North of Russia in the work of artists" in the Kola Scientific Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences. The main part of the exhibition were paintings from the funds of the Museum Archive of the city of Apatity, which served as illustrations for the book.[117]

The rivalry with A. Borisov was one of the main incentives for the young Nikolai Pinegin to choose polar themes. I. S. Sokolov-Mikitov argued that Pinegin was "the only artist who depicted with real truthfulness this airy, almost elusive beauty of the polar world". The writer noted that Pinegin conveyed the "tenderness of color" of polar nature, the subtle blues and emerald shimmers of the surface and texture of ice. He particularly emphasized the painting "Polar Rest," which depicts the "Foka" frozen in the ice. The depicted glow of the polar dawn on the snowdrifts symbolizes the doubt that there is still life on the icy ship.[118] In modern art criticism, the peculiarity of Pinegin's creative method is called "a deep understanding of polar nature, a heartfelt love for it, and a desire for accuracy in conveying the features of the northern landscape".[119] Lev Bogomolets claimed that Pinegin saved his soul, sincerity, and love for nature thanks to his "distance from the so-called artists who fill our 'creative' union".[120]

The first landscapes presented to the public in 1909-1910-ies ("Waterfall on the Tuloma River", "Kildin Island", "The northernmost village near Krestovaya Bay"), N. N. Efimov called "unpretentious" in color and even monotonous. However, these early works showed the development of the artistic method: the artist's desire for simplicity and maximum accuracy in conveying the nuances of the nature of the North.[122] On the contrary, the sketches made during Sedov's expedition are considered the best in his entire creative legacy. On each of his works, Pinegin added his signature, the date and the exact place where the picture was painted. The cycle of artistic works as a whole is a pictorial diary. For example, the remaining polar explorers during the campaign on Novaya Zemlya are depicted in the sketch "Northern Lights". Exhausted by the transition, people fell asleep on the snow, next to the sled, leaning against a block of ice gun and skis. Ghostly greenish shadows of the northern lights glide over them. The color solution in the "Rubini's Rock" sketch is also striking. It conveys the effects of the dim spring sun, which creates bluish reflections on the water, rocks, and ice surface. The study "Glacier Taisia" was done with great attention to detail, when the artist tried to give the oil colors the transparency of watercolors. The play of sunlight on the surface of snow and ice attracted Pinegin's attention in almost every work.[123] To convey the harsh nature of the Arctic, Pinegin used laconic artistic means. The coloring of his compositions is muted, he very subtly developed shades of restrained coloring of the nature of the North. The peculiarity of the northern plein air consists in the erasure of the boundaries of tones and halftones, the absence of bright color contrasts; the distant plans are sometimes clearer and sharper than the near ones. All these effects are present in the sketches of N. V. Pinegin.[124] The logic of the artist's development in 1917–1918 led to a greater generalization of forms (as in the painting "St. Foka in the Ice"), the color scheme became more decorative. His later landscapes of the second half of the 1930s were painted in a similar way.[125]

Nikolai Vasilyevich worked a lot in pencil and watercolor, in addition to oil painting. This part of his heritage is the least preserved. In the Crimea in 1916–1921 years he wrote many watercolors, by contrast, devoted to polar themes. In 1931 he independently designed his book "In the Land of the Arctic Foxes", making the headpieces and endpapers in ink.[126]

Nikolai Pinegin as a writer[edit]

N. Pinegin did not create literary works in the full sense of the word. However, his documentary essays and books are characterized by a bright and original style. Already his first notes from 1909 to 1910 are picturesque, detailed and entertaining. Pinegin, unlike S. Maximov or V. Nemirovich-Danchenko, did not abuse the peculiarities of the Pomor dialects (Pomors do not talk much); he described what he saw like an artist, paying attention to the terrain, the beauties of nature, the actions of people. For example: "on a steamship only first-class passengers get seasick. The common people like smelly fish, but if the carcass is dark, they will not eat it. In Kola the old way of life has been preserved, when men are still faithful to coat and undershirts, only young people wear jackets. When a traveler shot a partridge at a stop, his companions condemned him for wasting a bullet, noting that the bird could be "beaten with a stick".[127] Nikolai Pinegin was fascinated by the theme of northern mysticism and returned several times to the early story "At Padun". Padun is a taiga waterfall around which the heroes' actions unfold. The version included in "Notes of a Polar Researcher" was greatly simplified stylistically, and the theme of alcohol disappeared from it (probably to please the censors).[128]

The main books of N. Pinegin are usually called "Notes of a Polar Researcher" (in the expanded edition of 1952, compiled by I. Sokolov-Mikitov) and the edited diaries of the Sedov expedition "In the Icy Vast".[129] In addition to the strict documentary character, N. Pinegin's books were characterized by "vivid imagery, accurate knowledge of the northern nature", as well as "cheerful tone ... calling the younger generation to work and daring quests".[130] Konstantin Fedin, in an essay of the same year, summarized the work of Sokolov-Mikitov and Pinegin as "a restless call to move, to discover new things in life".[131]

Memory[edit]

The unpublished manuscripts of his friend V. Y. Wiese (1940) and his widow E. M. Pinegina (1978, 1980) are the main sources of N. V. Pinegin's biography.[132][133] Extensive essays were written by Ilya Brazhnin and Ivan Sokolov-Mikitov, who knew him.[134] The first monographic biography of the writer and artist was published in 2009 by A. N. Ivanov, an employee of the Elabuga State Historical, Architectural and Art Museum-Reserve.[135][136][137]

V. Pinegin is located in the Museum-Archive of the History of the Study and Development of the European North of the Center for Humanitarian Problems of the Barents Region of the Kola Scientific Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences, established in 1974 by the decision of the Presidium of the Geographical Society of the USSR at its Northern Branch in Apatity. In addition to book publications and manuscript diaries, the collection contains some of the artist's artistic works from various years, including the "Polar Cycle" of 1912–1914, as well as biographical evidence.[138] In the same collection was Pinegin's correspondence of the 1930s with foreign researchers, including V. Stefansson and V. Nobile, as well as a typewritten copy of the unfinished documentary novel "Georgy Sedov". Stefansson and U. Nobile, as well as a typewritten copy of the unfinished documentary novel "Georgy Sedov".[139][140] Part of the relics from the "St. Foka" E.M. Pinegina were transferred to the Central Naval Museum in 1964. The collection of items of maritime practice included a protractor, a hand-held compass and a German light meter (exponometer).[141] The Pushkin House has a personal collection of N. Pinegin (¹823), which includes printed editions of his works and the catalog of his solo exhibition in 1958. There are also drawings, sketches of costumes, sets for the plays "Eugene Onegin", "Boris Godunov" and others. In this fund there is a handwritten autobiography of Nikolai Vasilievich; a ticket of a member of the Union of Soviet Writers; a certificate of B.M. Shenfeld to the consular department of the USSR in Berlin about the non-involvement of N. V. Pinegin in the White movement in Russia; diaries of the expedition with G. Y. Sedov to the North Pole and to the Lyakhovskaya station.[142][110]

On March 14 (27), 1917 in Petrograd there was a preview of N. Pinegin's documentary "The Expedition of First Lieutenant Georgy Yakovlevich Sedov". A separate screening was soon held in Arkhangelsk. There are reports that the idea of the film and its editing polar explorer in the Crimea A. Khanzhonkov. The materials filmed by Pinegin became a working tool for Soviet polar explorers of the 1920-1930s and are used in documentary cinematography.[143] In 1974 Boris Grigoriev made the film "Georgy Sedov", where the role of N. V. Pinegin was played by V. A. Grammatikov.[144]

G. Y. Sedov named the westernmost island of the Southern Cross Islands and the western cape at the entrance to Inostrantsev Bay after Pinegin. Soviet explorers named a cape on Bruce Island in Franz Josef Land and a mountain in the Wohlthat Mountain in Antarctica after Pinegin. A lake in the north of Alexandra Land was named after N. V. Pinegin.[145] The name of the lake was approved by the Executive Committee of the Arkhangelsk Region in 1963.[146]

In 1985, the former Karlova Street in the Nevsky District of St. Petersburg was renamed as Pinegin Street. The renaming was due to the fact that it runs parallel to Georgiy Sedovo Street.[147][148] Writer Vladimir Lyakh in 2010 proposed to name one of the new streets in the Siedove settlement after Pinegin, which was accepted by the settlement council.[135]

Publications[edit]

- Айновы острова: Из путевых воспоминаний о Севере // Изв. Арханг. о-ва изучения Русского севера. — 1909. — № 13. — P. 61—74.

- Из сказок Лапландского Севера: Листки из записной книжки туриста // Изв. Арханг. о-ва изучения Русского севера. — 1910. — № 17. — P. 27—33.

- С Седовым к северному полюсу. — Берлин, 1923.

- В ледяных просторах: Экспедиция Г. Я. Седова к северному полюсу 1912–1914 г.. — Л. : Госиздат, 1924. — 272 с. — (Библиотека путешествий). — Приложение: В. Ю. Визе. Научные результаты экспедиции Г. Я. Седова. P. 263—267.

- Амундсен: Вступительный очерк // Амундсен Р. На крыльях в страну безмолвия: Путешествие к северному полюсу на аэроплане. — М.—Л., 1926. — P. 3—23.

- Путешествия к Северному полюсу // Рубакин Н. А. На плавающих льдинах к Ледовитому океану. — М.—Л., 1927—1928.

- Борьба за полюс // Жюль Верн и капитан Гаттерас: Его путешествия и приключения. — М.—Л., 1929. — P. 259—272.

- В стране песцов: Якутская АССР. — Л., 1932.

- Семьдесят дней борьбы за жизнь: По дневнику участника экспедиции Брусилова штурмана В. Альбанова. — Архангельск, 1932.

- Есипов В. К. (соавт.) Острова Советской Арктики: Новая Земля — Вайгач — Колгуев — Земля Франца Иосифа. — Архангельск, 1933.

- Новая Земля. — Архангельск, 1935. — (Острова Советской Арктики).

- Записки полярника. — Архангельск — М., 1936.

- Пинегин Н. В. Записки полярника. — 2-е изд.. — М.: Географгиз, 1952. — 496 p. Рец. на второе изд.: Болотинов Н. Арктика глазами художника // Новый мир. — 1952. — № 12. — P. 278—279.

- Полярный исследователь Г. Я. Седов. — Ростов н/Д : Ростиздат, 1940. — 472 p. — (Замечательные земляки).

- Георгий Седов: V. 1. — Л., 1941.

- Советское Заполярье: Лит.-худож. сб. к 20-летию освобождения Мурманского края от интервентов и белогвардейцев / Под ред. Ф. Бутцова, И. Бражникова, Н. Пинегина. — Л., 1941.

- Георгий Седов идёт к полюсу. — М., 1949.

- Георгий Седов. / Предисл. В. Ю. Визе. — 2-е изд. — М.—Л. : Изд-во Главсевморпути, 1953. — 351 p.

- Николай Васильевич Пинегин, 1883—1940: каталог выставки : Ленинградский союз советских художников / сост. и авт. вступ. ст. П. П. Ефимов. — Л. : Художник РСФСР, 1959. — 21, [1] p.

- Георгий Седов: Повесть для старшего школьного возраста. — Новосибирск, 1971.

- Пинегин Н. Лейтенант Седов идёт к полюсу // Живая Арктика. — 2003. — Май. — P. 130—135.

- В ледяных просторах : экспедиция Г. Я. Седова к Северному полюсу (1912—1914). — М. : Фонд поддержки экономического развития стран СНГ, 2008. — 302 p. — (Ломоносовская библиотека). — Посвящается 300-летию со дня рождения великого русского учёного и поэта Михаила Васильевича Ломоносова. — ISBN 978-5-94282-526-3.

- Пинегин Н. В. В ледяных просторах. Экспедиция Г. Я. Седова к Северному полюсу (1912—1914). — М.: ОГИ, 2009. — 304 p. — ISBN 978-5-94282-526-3.

- В ледяных просторах. Записки полярника. — М. : Эксмо, 2021. — 448 p. — ISBN 978-5-04-110869-4.

Notes[edit]

- ^ See the main article on this topic: Российский государственный музей Арктики и Антарктики

References[edit]

- ^ Поморская энциклопедия: В 5 т. Т. I: История Архангельского Севера / Гл. редактор В. Н. Булатов; Сост. А. А. Куратов. — Архангельск: Поморский университет, 2001. — P. 304.

- ^ Иванов А. Н. Николай Пинегин: очарованный Севером. — Елабуга: Елабужский гос. историко-архитектурный и худож. музей-заповедник, 2009. — 272 p. — P. 268-269. — ISBN 978-5-91607-030-9.

- ^ Иванов А. Н. Николай Пинегин: очарованный Севером. — Елабуга: Елабужский гос. историко-архитектурный и худож. музей-заповедник, 2009. — 272 p. — P. 10-12. — ISBN 978-5-91607-030-9.

- ^ a b c d e Вехов Н. В. (3 May 2014). "Северный мир художника Николая Пинегина. Искусства и ремесла Кольского Севера". Archived from the original on 13 April 2021.

- ^ Прилепина О. Странная земля // Русский мир. — 2013. — Сентябрь. — P. 29.

- ^ Агапов М. Г., Клюева В. П. «Север зовёт!»: мотив «северное притяжение» в истории освоения Российской Арктики // Сибирские исторические исследования. — 2018. — № 4. — P. 9-10. — doi:10.17223/2312461X/22/1.

- ^ Капинос Е. В., Лощилов И. Е. Кнут Гамсун в Сибири // Критика и семиотика. — 2020. — № 2. — P. 317, 321. — ISSN 2307-1737.

- ^ Пинегин Н. В. Записки полярника. — 2-е изд.. — М.: Географгиз, 1952. — 496 p. — P. 13.

- ^ Иванов А. Н. Николай Пинегин: очарованный Севером. — Елабуга: Елабужский гос. историко-архитектурный и худож. музей-заповедник, 2009. — 272 p. — P. 13-14, 16. — ISBN 978-5-91607-030-9.

- ^ Пинегин Н. В. Записки полярника. — 2-е изд.. — М.: Географгиз, 1952. — 496 p. — P. 13-14.

- ^ Пинегин Н. В. Записки полярника. — 2-е изд.. — М.: Географгиз, 1952. — 496 p. — P. 16.

- ^ Соколов-Микитов И. С. Полярный художник [Н. В. Пинегин] // Давние встречи : воспоминания. — Л. : Советcкий писатель, 1976. — P. 182. — 318 p.

- ^ Иванов А. Н. Николай Пинегин: очарованный Севером. — Елабуга: Елабужский гос. историко-архитектурный и худож. музей-заповедник, 2009. — 272 p. — P. 16-19. — ISBN 978-5-91607-030-9.

- ^ Иванов А. Н. Николай Пинегин: очарованный Севером. — Елабуга: Елабужский гос. историко-архитектурный и худож. музей-заповедник, 2009. — 272 p. — P. 19. — ISBN 978-5-91607-030-9.

- ^ Вехов Н. В. «Страна чудес — волшебный Север». О ныне практически забытом полярнике Николае Васильевиче Пинегине (1883—1940) // Московский журнал. — 2011. — № 3 (243) (март). — P. 15.

- ^ Иванов А. Н. Николай Пинегин: очарованный Севером. — Елабуга: Елабужский гос. историко-архитектурный и худож. музей-заповедник, 2009. — 272 p. — P. 19-21. — ISBN 978-5-91607-030-9.

- ^ Иванов А. Судьбоносная статья Николая Пинегина. ГБУК «Елабужский государственный историко-архитектурный и художественный музей-заповедник» (23 May2018).

- ^ Николай Васильевич Пинегин, 1883—1940: каталог выставки : Ленинградский союз советских художников / сост. и авт. вступ. ст. П. П. Ефимов. — Л. : Художник РСФСР, 1959. — P. 4.

- ^ Иванов А. Н. Николай Пинегин: очарованный Севером. — Елабуга: Елабужский гос. историко-архитектурный и худож. музей-заповедник, 2009. — 272 p. — P. 19-25. — ISBN 978-5-91607-030-9.

- ^ a b Вехов Н. В. «Страна чудес — волшебный Север». О ныне практически забытом полярнике Николае Васильевиче Пинегине (1883—1940) // Московский журнал. — 2011. — № 3 (243) (март). — P. 7.

- ^ Иванов А. Н. Николай Пинегин: очарованный Севером. — Елабуга: Елабужский гос. историко-архитектурный и худож. музей-заповедник, 2009. — 272 p. — P. 25-27. — ISBN 978-5-91607-030-9.

- ^ Иванов А. Н. Николай Пинегин: очарованный Севером. — Елабуга: Елабужский гос. историко-архитектурный и худож. музей-заповедник, 2009. — 272 p. — P. 27-29. — ISBN 978-5-91607-030-9.

- ^ Маркин В. Русские полярные экспедиции 1912—1914 годов // Наука в России. — 2012. — № 4. — P. 82.

- ^ Иванов А. Н. Николай Пинегин: очарованный Севером. — Елабуга: Елабужский гос. историко-архитектурный и худож. музей-заповедник, 2009. — 272 p. — P. 30-31. — ISBN 978-5-91607-030-9.

- ^ Пинегин Н. В. В ледяных просторах. Экспедиция Г. Я. Седова к Северному полюсу (1912—1914). — М.: ОГИ, 2009. — P. 8-10. — 304 p. — ISBN 978-5-94282-526-3.

- ^ В ледяных просторах: Экспедиция Г. Я. Седова к северному полюсу 1912–1914 г.. — Л. : Госиздат, 1924. — 272 p. — (Библиотека путешествий). — Приложение: В. Ю. Визе. Научные результаты экспедиции Г. Я. Седова. P. 75.

- ^ Иванов А. Н. Николай Пинегин: очарованный Севером. — Елабуга: Елабужский гос. историко-архитектурный и худож. музей-заповедник, 2009. — 272 p. — P. 34-35. — ISBN 978-5-91607-030-9.

- ^ Пинегин Н. В. В ледяных просторах. Экспедиция Г. Я. Седова к Северному полюсу (1912—1914). — М.: ОГИ, 2009. — P. 24. —304 p. — ISBN 978-5-94282-526-3.

- ^ Иванов А. Н. Николай Пинегин: очарованный Севером. — Елабуга: Елабужский гос. историко-архитектурный и худож. музей-заповедник, 2009. — 272 p. — P. 39-40. — ISBN 978-5-91607-030-9.

- ^ Пинегин Н. В. В ледяных просторах. Экспедиция Г. Я. Седова к Северному полюсу (1912—1914). — М.: ОГИ, 2009. — P. 49-50. — 304 p. — ISBN 978-5-94282-526-3.

- ^ Пинегин Н. В. В ледяных просторах. Экспедиция Г. Я. Седова к Северному полюсу (1912—1914). — М.: ОГИ, 2009. — P. 74. — 304 p. — ISBN 978-5-94282-526-3.