History of the eastern steppe

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

This article summarizes the History of the eastern steppe, the eastern third of the Eurasian Steppe, that is, the grasslands of Mongolia and northern China. It is a companion to History of the central steppe and History of the western steppe. Most of its recorded history deals with conflicts between the Han Chinese and the steppe nomads. Most of the sources are Chinese.

Geography[edit]

The area is bounded on the north by the forests of Siberia, on the east by mountains along the Pacific coast, on the southeast by a small area of agricultural China, on the south by the Tibetan plateau and on the west by the mountains along the former Sino-Soviet border. Between these mountains and Siberia the so-called Dzungarian Gate opens out onto the vast Kazakh steppe to the west.

The area has three parts: Manchuria, Mongolia and Dzungaria. The core of the area is Mongolia, not only the Outer Mongolia that is seen on maps but also Inner Mongolia and much of Gansu which are now part of China. The Gobi Desert or semi-desert separates Outer and Inner Mongolia. The best grazing lands are in the north around such places as the Orkhon River and Onon Rivers. To the east the steppe extends into "Manchuria" but does not reach the coast because of mountains and moisture from the Pacific. The Manchurian steppe merges northward to a deciduous forest-steppe and then the coniferous forest of Siberia. To the south it merges into agricultural China. In the west Dzungaria or northern Xinjiang is a westward extension of Mongolia. To the west of that the Dzungarian Gate leads to the extensive steppes of Kazakhstan, particularly the region of Jetysu.

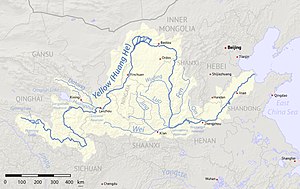

In the southeast is the agricultural area of the North China Plain, roughly around Beijing and southward. West of that are the mountains of Shanxi (the name means "western mountains"). West of the mountains is the Ordos Loop of the Yellow River. On the southern side of the Ordos country is the Wei River valley which was long a center of Chinese civilization. The northern Ordos region is semi-desert and part of Inner Mongolia. The area was often disputed between agricultural China and the steppe nomads. West of that is the long and narrow Gansu Corridor. It is bounded on the south by the high and desolate Tibetan plateau and on the north by the grasslands of Mongolia. Along it is a chain of oases which form a natural caravan route from China westward. At the west end of the Gansu corridor is the oval Tarim Basin with its central desert and ring of oases around the edges. The Tarim is desert rather than steppe but interacted with the steppe in various ways. At the west end of the Tarim Basin passes lead over the mountains south to India and west to central Asia, Persia and Europe. The Gansu-Tarim route was the main axis of the Silk Road that connected China with the rest of the world. When Chinese dynasties were strong they would often extend a finger of power along the Gansu corridor into the Tarim Basin. When the nomads were strong they would try to control, tax or loot the Gansu-Tarim region.

On the northern edge can be noted the forest-steppe of north Manchuria and west of that the thinly-populated mountains of Transbaikalia. Around Lake Baikal the forest and steppe peoples have tended to blend, producing the modern Buryats. West of that is the Altai-Sayan region noted for its metalwork, especially the Minusinsk Basin.

Historical outline[edit]

A note on ethnonyms: Most of steppe history consists of statements like "in a certain year people A replaced people B." These "peoples" are usually some dynasty, clan or tribe that gained control over its neighbors and became militarily or politically significant. Borders were ill-defined and fluctuated, as did the ruler's power. Daily life went on without much regard to whoever was in power. "Replacement" usually means a mere change of ruling group, but sometimes involved a genuine folk migration or change in language or religion. Since historical records depend on scattered reports from neighboring literate societies, there is substantial uncertainty especially in the early period.

Early period[edit]

Civilization emerged in north China in the second millennium BC. At this time the Tarim Basin was inhabited by people of European appearance who probably spoke an Indo-European language (Tocharian). They may have introduced the chariot and bronze-working into China. The later Yuezhi in the Gansu corridor may have also been Tocharian. The origin of steppe pastoral nomadism is not well understood. Mounted archery began in the west and reached east Asia some time before 307 BC. The steppes were inhabited by various disunited tribes that the Chinese called Rong (west), Beidi (north), Donghu (east) and other names.

Han and Xiongnu (206 BC-220 AD)[edit]

In 221 BC, China proper was unified by the Qin dynasty and after a brief civil war, more permanently by the Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD). About 209 BC the steppe tribes were united by the Xiongnu. The two unifications were connected in that the nomads had to unite to protect themselves from the powerful Han dynasty and the Xiongnu ruler could strengthen himself with Han tribute. In the east, the Xiongnu conquered the Donghu in Manchuria and in the west they drove the Wusun and Yuezhi westward. The Wusun soon disappeared, but the Yuezhi later had a great career as the Kushans of Afghanistan. After about 75 years of internal consolidation and external tribute, the Emperor Wu of Han adopted a forward policy. Zhang Qian went west (138-125 BC) and returned with the first good reports of the Western Regions. During the Han-Xiongnu Wars the southern Xiongnu in Inner Mongolia were subjugated and the northern Xiongnu were driven to northern Mongolia where they were broken up around 89 AD. The Han gained control of the Gansu Corridor and the Tarim Basin with some influence westward. This opened the Silk Road and led to the appearance of Chinese silk in the Roman Empire. As the Han dynasty declined, the Tarim Basin experienced complex shifts of power between the Han, Xiongnu remnants and local rulers.

Xianbei, Rouran and Turk (220–840)[edit]

- 220–589: China disunited: From the fall of the Eastern Han until the reunification of China proper under the Sui dynasty, northern China was usually ruled by short-lived dynasties of steppe origin, known in historiography as the Sixteen Kingdoms and Northern and Southern dynasties periods. During this period, Buddhism spread from northern India north to the Tarim Basin and east along the Gansu corridor to China.

- 93–234: Xianbei: The Mongolic Xianbei (former Donghu) spread from Manchuria and ruled the steppes as the Xianbei state. They were defeated by the short-lived Cao Wei dynasty which had some control over Gansu.

- 402–552: Rouran: A branch of the Xianbei reunited the Mongolian Plateau as the Rouran Khaganate. The Rouran were the first to use the title Khagan or Khan.

- 589–907: Sui and Tang dynasties: China proper was reunited by the short-lived Sui dynasty followed by the longer-lived Tang dynasty (618–907) which regained the Tarim Basin, entered the Pamirs and fought the expanding Muslims at the Battle of Talas in 751.

- 552–744:Turkic Khaganate: The Gokturks lived in the Altai region, engaged in metalwork and were subjects of the Rouran. They were the first ruling group who were clearly Turkic (Orkhon Inscriptions). In 552, they overthrew the Rouran and established the First Turkic Khaganate which extended far to the west. After about 25 years, the western half broke off, which marks the beginning of the Eastern Turkic Khaganate. This lasted from 581 to 630, was conquered by the Tang dynasty (630–682), and was later restored (682–744).

- 744–840 Uighurs: These Turkic people lived around Lake Baikal and were probably descended from the Tiele and earlier Dingling. They founded the Uyghur Khaganate and were much influenced by Sogdian merchants from central Asia. In the twentieth century their name was given to the Turkic inhabitants of the Tarim Basin.

- 840-?: Kirghiz: The Yenisei Kirghiz came from the southern Yenisey and closely related to Turkic Khakas and Fuyu Kyrgyz people. They overthrew the Uighurs with help from the Tang dynasty, but never formed a great empire.

Mongols and Manchus (907–1912)[edit]

- 916–1125 Khitans and Liao dynasty: The Mongolic Khitans founded the Liao dynasty in 916. After the collapse of the Liao in 1125, remnants fled west and formed the Western Liao dynasty.

- 1125–1234: Jurchens and Jin dynasty: The Jurchens were a Tungusic forest people in northern Manchuria. They established the Jin dynasty in 1115 and overthrew the Liao dynasty in 1125. Southern China remained under the Song dynasty.

- 982–1227: Tanguts and Western Xia dynasty: The Tibetan Tanguts controlled the Gansu corridor and established the Western Xia dynasty.

- 1206–1368 Mongols and Yuan dynasty: In 1206, the Mongol tribes were united by Genghis Khan who captured north China and most of central Asia. His sons and grandsons took Manchuria, south China, Persia and Russia forming the Mongol Empire. It split into four parts, with the Yuan dynasty ruling over the eastern steppe. Western Xinjiang was ruled from central Asia by the Chagatai Khanate.

- 1368–1644 Ming dynasty: The Ming dynasty defeated the Yuan dynasty, forcing the latter to retreat north, thus forming the Northern Yuan dynasty.

- 1636–1912 Manchus and Qing dynasty: A group of Jurchens took the name Manchu established the Qing dynasty. Its westward expansion is noted under Dzungars below.

- 1582–present: Russia: From 1582 Russian adventurers made themselves masters of the Siberian forests. The Chinese border with Russia at Manchuria and Outer Mongolia was defined in 1689 and 1727 respectively.

- 1620–1759 Dzungars: Around 1620 the western Mongols established the Dzungar Khanate in Dzungaria which was the last of the steppe empires. In 1696 they were driven out of Outer Mongolia which fell to the Qing dynasty. In 1720 they were driven out of Tibet which became part of the Qing dynasty. In 1759 Dzungaria was conquered by the Chinese who then moved south to the Tarim Basin, thereby completing the current western border of China. Dzungaria and the Tarim Basin were combined for the first time as the province of Xinjiang.

Recent period[edit]

In the 19th century Western imperialism and industrialism began to impact eastern Asia. Steppe nomadism and many traditional Chinese institutions gradually became obsolete, both economically and militarily. In 1860 Russia annexed north and east Manchuria which soon acquired a Russian population. There was a massive migration of Han Chinese into Manchuria and Inner Mongolia which socially removed these areas from the steppe and attached them to China. When the Manchu dynasty fell in 1912 the Mongols claimed that they had been subject to the Manchus rather than China and were therefore now independent. This Russian-backed independence may have prevented Chinese immigration into the area. In recent decades there has been a significant Han migration into Xinjiang.

See also[edit]

- History of the central steppe

- History of the western steppe

- Bibliography of the history of Central Asia

Sources[edit]

- Rene Grousset, The Empire of the Steppes, 1970

- Denis Sinor (editor), The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, 1990

- Cristoph Baumer, The History of Central Asia, 2012--, 3 volumes

- Sources in the linked articles. There appears to be no book devoted specifically to the whole history of the eastern steppe.