Qiupalong

| Qiupalong Temporal range: Late Cretaceous

~72 to 66 Ma - | |

|---|---|

| |

| The holotype specimen on display in China | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | †Ornithomimosauria |

| Family: | †Ornithomimidae |

| Genus: | †Qiupalong Xu et al., 2011 |

| Type species | |

| †Qiupalong henanensis Xu et al., 2011

| |

Qiupalong (meaning "dragon from the Qiupa Formation") is an extinct genus of ornithomimosaurian theropod that was discovered in the Late Cretaceous Qiupa Formation of Henan, China. The genus contains a single species, Q. henanensis, the specific epithet for which was named for the province of Henan.[1] Uniquely, Qiupalong is one of the few Late Cretaceous non-avian dinosaurs known from both Asia and Laramidia. Specimens from Russia and Alberta have been referred to the genus without being assigned to the type species.[2][3]

Discovery[edit]

The Qiupa Formation is located in the Tantou Basin which is in Luanchuan County of the Henan province in China. Lithological correlation of the local strata has dated the Qiupa Formation to the Late Cretaceous.[1] More specific analyses have suggested that the formation dates to the end of the Maastrichtian stage, which was the final stage of the Mesozoic Era.[4] This would make Qiupalong and its contemporaries were among the last-surviving non-avian dinosaurs.[5]

The Qiupa Formation preserves a wide variety of dinosaur eggs, many of which have been named as ootaxa, as well as body fossils. Qiupalong was the first ornithomimosaur to be discovered in the area, and when it was described, it added to the known diversity of Asian ornithomimosaurs of the Late Cretaceous. It was described in 2011 by a team of scientists from various institutions in China, South Korea, Japan, and Canada which included Li Xu, Yoshitsugu Kobayashi, Junchang Lü, Yuong-Nam Lee, Yongqing Liu, Kohei Tanaka, Xingliao Zhang, Songhai Jia, and Jiming Zhang. The holotype consists of a partial postcranial skeleton and is housed in the Henan Geological Museum and was given the designation HGM 41HIII-0106.[1]

In 2017, another team of researchers including Philip J. Currie, described some postcranial ornithomimid remains from the Belly River Group in Alberta, Canada. These included the specimens UALVP 53595 and UALVP 52861 from the Dinosaur Park Formation and CMN 8902. The latter specimen was discovered in 1921 before the delineation between the Dinosaur Park and Oldman formations was erected, and the precise locality from which it was collected is not certain. Therefore, the specimen's precise age is also uncertain.[2]

When these newer specimens were described, the authors noted that they bore significant morphological similarities to the holotype of Qiupalong. The foot claws of the new specimens in particular were nearly identical to those of the holotype. As a result, they referred these new remains to the genus, but they did not assign it to the type species. The significance of this referral was noted by the authors. It extended the temporal range of Qiupalong from the middle Campanian to the latest Maastrichtian - a span of roughly 10 million years. This would also make Qiupalong the only genus of ornithomimid known from both Asia and Laramidia.[2]

In 2023, the tibia of a juvenile ornithomimosaur from the Udurchukan Formation of the Amur Oblast in the Russian Far East was described by Alexander Averianov and colleagues. The tibia is believed to be from the end of the Maastrichtian, and the authors noted that its morphology was very similar to Qiupalong. It was also found in a region of Russia that preserves hadrosaurs of North American affinities. They hypothesized that it was from an animal very similar to Qiupalong which may have participated in a faunal dispersal from North America to Asia. However, Averianov and colleagues did not refer the remains to any specific genus within ornithomimidae.[3]

Description[edit]

Qiupalong was very similar to derived North American ornithomimosaurs like Ornithomimus and Struthiomimus. Xu and colleagues gave lengths for the pubis, tibia, and metatarsals as 320 millimetres (13 in), 384 millimetres (15.1 in), and 233 millimetres (9.2 in) respectively.[1] They did not give an estimate for the animal's overall size,[1] but Rubén Molina-Pérez and Asier Larramendi suggested a length of 2.85 metres (9.4 ft) and a mass of 63 kilograms (139 lb).[6]

Xu and colleagues diagnosed the genus by the following apomorphies: a notch on the medial posterior process of the tibia, a small pit near the articular surface between the astragalus and calcaneum, a short anterior extension of the pubic boot, an arctometatarsalian condition of the third metatarsal, a straight pubic shaft, and a wide angle between the pubic shaft and boot. Some of these are autapomorphies, while others are plesiomorphic characteristics or synapomorphic traits shared with other ornithomimids.[1]

Holotype[edit]

The holotype of Qiupalong, given the designation HGM 41HIII-0106, consists of several disarticulated bones from the postcranial skeleton. These include both ilia, both pubes, parts of both ischia, as well as the tibia, all three metatarsals, a phalanx, and a pedal ungual from the right hindlimb. These bones are not confidently assigned to a single animal, but the size of the bones relative to one another suggests that they come from a minimum of two similarly-sized animals.[1]

The taphonomic conditions vary for the different bones of the holotype. The pelvic elements are crushed and not completely preserved, and the right side of these bones are more intact than those of the left side. The leg bones are mostly complete and several of the ankle elements were partially articulated.[1]

In comparison to other ornithomimids, Qiupalong has a mix of derived and plesiomorphic features. The toe claws are curved downwards, which resembles the condition seen in basal ornithomimosaurs and is unlike other derived ornithomimids from Asia. The metatarsals display the arctometatarsalian condition, and they are almost identical to the other derived ornithomimids including Ornithomimus, Struthiomimus, and Gallimimus. The shape of the pubis is also more similar to ornithomimids from North America than it is to non-ornithomimid ornithomimosaurs like Shenzhousaurus and Harpymimus.[1]

In their description of the holotype, Xu and colleagues made numerous comparisons to the holotype of the tyrannosauroid Alectrosaurus (which is a single partial hindlimb) because ornithomimosaur and tyrannosauroid legs bear a number of superficial similarities. Although these similarities unite these groups in morphology to the exclusion of other coelurosaurs, the specific morphology of Qiupalong clearly identifies it as an ornithomimosaur.[1]

Referred material[edit]

Several ornithomimosaur specimens recovered from the Belly River Group in Alberta had not been assigned to any particular genus on their initial discovery. In 2017, a team of authors led by Bradly McFeeters revisited these specimens and referred several of them to the recently described genus, Qiupalong. These specimens included CMN 8902 (vertebrae, ribs, scapulocoracoid, partial limb bones, and hip bones), UALVP 53595 (an ankle bone), UALVP 52861 (pedal ungual).[2]

The UALVP specimens were from the Dinosaur Park Formation and the CMN specimen was from an uncertain locality east of the Little Sandhill Creek locality, which may have been a part of the Oldman Formation, although the authors are not certain. The CMN specimen was collected by Charles M. Sternberg before the Dinosaur Park and Oldman formations were split into two distinct geological units, and the notes he gave were not sufficient to identify exactly from which locality he collected CMN 8902.[2]

These specimens were referred to Qiupalong sp. because they were not diagnostic to the species level, but they strongly resembled some of the bones of the holotype of Q. henanensis. In particular, UALVP 52861 (a pedal ungual) was noted to be almost identical in morphology to those known from the holotype. However, McFeeters and colleagues noted that several of the bones of CMN 8902 were not able to be compared with the holotype of Qiupalong because the specimen consists of bones that are not present in the holotype (the vertebrae and bones of the arm). The authors also note that the morphology of these elements is broadly similar to other North American ornithomimosaurs and if CMN 8902 is an individual of Qiupalong, it supports a close relationship with Struthiomimus and Ornithomimus.[2]

McFeeters and colleagues also remark that one of the listed autapomorphies for the type species of Qiupalong (a notch on the medial posterior process of the tibia) may not be a true autapomorphy because a similar condition is present in the specimen TMP 1994.012.1010, which has not been referred to any particular species. They also remark that, because of the poor preservation conditions of many ornithomimosaur fossils, it is difficult to determine whether or not other taxa possessed this trait.[2]

Most recently, in 2023, Alexander Averianov and colleagues published a description of the tibia of a juvenile ornithomimosaur, which they stated bears considerable similarity to the holotype of Qiupalong henanensis. This specimen was found at the Kundur locality of the Udurchukan Formation, which is in the Amur Oblast of the Russian Far East. It was the first material of an ornithomimosaur to be described from this locality, which had previously only yielded theropod remains from dromaeosaurids, tyrannosaurids, and the enigmatic Ricardoestesia. The locality itself is known primarily for hadrosaur fossils, including the Olorotitan and Kundurosaurus.[3]

The specimen itself, AEIM 2/1045, was sectioned for histological study to determine its ontogenetic age. Averianov and colleagues suggested, based on the presence of active secondary remodeling and the lack of an external fundamental system, that the individual was a young adult which was still actively growing when it died. They do not specifically refer it to Qiupalong, but they do remark that it bears the most similarity to it out of all ornithomimids.[3]

Classification[edit]

In their description of the holotype, Xu and colleagues performed a phylogenetic analysis based on the dataset compiled by Yoshitsugu Kobayashi and Jun−Chang Lü in their description of Sinornithomimus in 2003.[7] They added character information for several newly discovered taxa and ran their analysis using 47 unordered characters assigned to 14 taxa, and their analysis included Allosaurus and several tyrannosaurids as outgroups.[1]

They recovered Qiupalong in a clade with Struthiomimus and Ornithomimus, which they refer to as the "North American clade" (after Kobiyashi and Lü who recovered the same clade). This clade is diagnosed by a very acute angle between pubic shaft and boot and a tip of anterior extension of the pubic boot. They also comment on the discovery of some material from the Dinosaur Park Formation, that may also belong to this clade.[1] This material would later be described and referred to "Qiupalong sp.".[2]

| Ornithomimosauria |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

More recent phylogenetic analyses have recovered mostly similar positions for Qiupalong (i.e. in a derived position closely-related to North American taxa). Examples of such analyses include Brusatte and colleagues (2014),[8] Serrano-Brañas and colleagues (2020),[9] and Hattori and colleagues (2023).[10]

Averianov and Dieter-Sues recovered a slightly different phylogeny[11] using the data set produced by Jonah Choiniere and colleagues in 2012.[12] They recovered Anserimimus as being part of the "North-American clade" as the sister taxon of Ornithomimus and Struthiomimus as being the most basal member of this clade. The results of their analysis are shown below.[11]

| Ornithomimidae |

| ||||||||||||

Paleoecology[edit]

Diet[edit]

The skull of Qiupalong is not known, although it is assumed that it was likely similar to other ornithomimids in being edentulous and having a beak.[1][2] As such, no concrete hypotheses of the animal's diet have been made, although Cullen and colleagues suggested that it probably had a similar diet to other ornithomimids like Ornithomimus and Struthiomimus and may have even coexisted alongside them with minimal competition.[13]

Evolution and dispersal[edit]

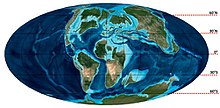

Although the first remains of Qiupalong to be described were from Asia, the geologically oldest remains from the genus are from Laramidia. This, coupled with the results of several phylogenetic analyses, suggest that Qiupalong originated in North America and only migrated into Asia later, near the very end of the Cretaceous Period.[2] This is consistent with the suggestion by other researchers that significant faunal interchange took place during the Campanian and Maastrichtian stages between the two continents via the Bering Land Bridge, which has its origins in the Cretaceous.[3]

Qiupalong is not the only genus to exist on both continents. Both Saurolophus and Parasaurolophus (or possibly Charonosaurus) are known to have migrated from North America to Asia. Furthermore, it has been suggested that animals like Sinoceratops, Olorotitan, and Tarbosaurus are the descendants of animals which immigrated to Asia during this period. The exact time that this migration occurred is uncertain because the geochronology of Cretaceous Asia has not been studied as thoroughly as the geochronology of North America.[3][14]

Paleoenvironment[edit]

- Belly River Group

The exact age of the North American specimens of Qiupalong is not confidently known. However the ages of the Oldman Formation and the Dinosaur Park Formation as a whole is relatively confidently known to have been deposited between 79.50 and 75.46 million years ago.[14]

The Dinosaur Park and Oldman formations are composed of sediments that were derived from the erosion of the mountains to the west. They were deposited on an alluvial to coastal plain by river systems that flowed eastward and southeastward to the Bearpaw Sea, a large inland sea that was part of the Western Interior Seaway. That sea gradually inundated the adjacent coastal plain, depositing the marine shales of the Bearpaw Formation on top of the Dinosaur Park Formation, which is in turn on top of the Oldman Formation.[15]

- Qiupa Formation

The Qiupa Formation is subdivided into three sections laterally, which correspond to different outcroppings of the rock layer. Section A, in which Qiupalong was found, is subdivided into 60 distinct beds, which themselves are numbered in ascending order from oldest to youngest. Qiupalong was found in "bed 34", which is intermediate in age relative to the sediments of the formation as a whole and is the locality from which a majority of the formation's dinosaur body fossils have been recovered.[4][16] Beds 21 through 41 — which are grouped together in the description of the stratigraphy of the Qiupa Formation — are composed primarily of purple calcareous siltstone and calcareous mudstone. This sedimentary layer would have been deposited by a braided river delta that created the depositional environment necessary for fossils to form.[4] This area is also interpreted as having been part of a coastal environment during the end of the Cretaceous Period.[16]

Contemporary fauna[edit]

- Belly River Group

The earliest record of Qiupalong is from either the Oldman Formation or the Dinosaur Park Formation.[2] The Dinosaur Park Formation is one of the most well-studied paleoenvironments in the world. Dozens of species are known from various parts of the formation including massive tyrannosaurids, hadrosaurids, ceratopsids, and ankylosaurs in addition to a variety of smaller dinosaurs like leptoceratopsids, pachycephalosaurids, dromaeosaurs, caenagnathids, troodontids, and other ornithomimosaurs.[13]

The remains of Qiupalong are from differing localities, some of which are unknown, but most of the material that is confidently assigned to individual localities are from the lower half of the Dinosaur Park Formation, about 20 meters above the contact with the Oldman Formation.[1] This corresponds to what has been called "Megaherbivore Assemblage Zone 1", the "Sandy zone", or the "Centrosaurus-Corythosaurus zone". This faunal stage would have obviously included Centrosaurus and Corythosaurus, but other animals from this time period included Euoplocephalus, Dyoplosaurus, Panoplosaurus, Chasmosaurus, Lambeosaurus, and Parasaurolophus.[14][17] These herbivores would have been preyed upon by the tyrannosaurids Gorgosaurus and Daspletosaurus, which are known to have coexisted.[18]

Small dinosaurs in general appear to have overlapped in their temporal distribution much more significantly. Most remains from small theropods are from the lower half of the Dinosaur Park Formation, where the remains of Qiupalong are believed to have originated. Qiupalong is believed to have coexisted with Ornithomimus and possibly also Struthiomimus. It has also been hypothesized that they may have formed multi-species assemblages, analogous to bovids in Africa today. Qiupalong also likely coexisted with the three known caenagnathids from the area, Citipes, Chirostenotes, and Caenagnathus.[13]

- Qiupa Formation

The Qiupa Formation is very fossil rich, although only a few species excavated from the area have been described. The largest inhabitants of the area were the non-avian dinosaurs. Remains of large dinosaurs are fragmentary and indeterminate in identity, with many of them only being diagnostic to the family level. Partial remains from the area have been attributed to ankylosaurids and tyrannosaurids, and one of these was even named: the dubious "Tyrannosaurus luanchuanensis".[4] More complete remains are known from small theropods. Qiupalong was contemporaneous with the alvarezsaur Qiupanykus,[19] the dromaeosaur Luanchuanraptor,[4] indeterminate troodontids,[1] and the oviraptorid Yulong.[20]

This environment was also home to a variety of other animals. These would have included turtles, lizards (such as the genus Tianyusaurus), small mammals, and uniquely an edentulous enantiornithine Yuornis.[4][21]

See also[edit]

- 2011 in archosaur paleontology

- Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event

- Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology

- List of Asian dinosaurs

- Timeline of ornithomimosaur research

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Li Xu; Yoshitsugu Kobayashi; Junchang Lü; Yuong-Nam Lee; Yongqing Liu; Kohei Tanaka; Xingliao Zhang; Songhai Jia; Jiming Zhang (2011). "A new ornithomimid dinosaur with North American affinities from the Late Cretaceous Qiupa Formation in Henan Province of China". Cretaceous Research. 32 (2): 213–222. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2010.12.004.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l McFeeters, B.; Ryan, M.J.; Schröder-Adams, C.; Currie, P.J. (2017). "First North American occurrences of Qiupalong (Theropoda: Ornithomimidae) and the palaeobiogeography of derived ornithomimids". FACETS. 2: 355–373. doi:10.1139/facets-2016-0074.

- ^ a b c d e f Averianov, Alexander; Skutschas, Pavel; Bolotsky, Yuriy; Bolotsky, Ivan (2023-12-31). "First find of an ornithomimid theropod dinosaur in the Upper Cretaceous of the Russian Far East". Biological Communications. 68 (4). doi:10.21638/spbu03.2023.405. ISSN 2587-5779.

- ^ a b c d e f Jiang, X.-J.; Liu, Y.-Q.; Ji, S.-A.; Zhang, X.-L.; Xu, L.; Jia, S.-H.; Lü, J.-C.; Yuan, C.-X.; Li, M. (2011). "Dinosaur-bearing strata and K/T boundary in the Luanchuan-Tantou Basin of western Henan Province, China". Science China Earth Sciences. 54 (1149). doi:10.1007/s11430-011-4186-1.

- ^ Han, Fei; Wang, Qiang; Wang, Huapei; Zhu, Xufeng; Zhou, Xinying; Wang, Zhixiang; Fang, Kaiyong; Stidham, Thomas A.; Wang, Wei; Wang, Xiaolin; Li, Xiaoqiang; Qin, Huafeng; Fan, Longgang; Wen, Chen; Luo, Jianhong; Pan, Yongxin; Deng, Chenglong (2022). "Low dinosaur biodiversity in central China 2 million years prior to the end-Cretaceous mass extinction". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 119 (39). Bibcode:2022PNAS..11911234H. doi:10.1073/pnas.2211234119. PMC 9522366. PMID 36122246.

- ^ Molina-Pérez, Rubén; Larramendi, Asier (2019). Dinosaur Facts and Figures: The Theropods and Other Dinosauriformes. Translated by Connolly, David; Ramírez Cruz, Gonzalo Ángel. Illustrated by Andrey Atuchin and Sante Mazzei. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691180311.

- ^ Kobayashi, Yoshitsugu; Lü, Jun−Chang (2003). "A new ornithomimid dinosaur with gregarious habits from the Late Cretaceous of China". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 48 (2): 235–259.

- ^ Brusatte, Stephen L.; Lloyd, Graeme T.; Wang, Steve C.; Norell, Mark A. (2014). "Gradual Assembly of Avian Body Plan Culminated in Rapid Rates of Evolution across the Dinosaur-Bird Transition" (PDF). Current Biology. 24 (20): 2386–2392. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.08.034. PMID 25264248. S2CID 8879023.

- ^ Serrano-Brañas, Claudia Inés; Espinosa-Chávez, Belinda; MacCracken, S. Augusta; Gutiérrez-Blando, Cirene; De León-Dávila, Claudio; Ventura, José Flores (2020). "Paraxenisaurus normalensis, a large deinocheirid ornithomimosaur from the Cerro del Pueblo Formation (Upper Cretaceous), Coahuila, Mexico". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 101. Bibcode:2020JSAES.10102610S. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2020.102610. S2CID 218968100.

- ^ Hattori, S.; Shibata, M.; Kawabe, S.; Imai, T.; Nishi, H.; Azuma, Y. (2023). "New theropod dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Japan provides critical implications for the early evolution of ornithomimosaurs". Scientific Reports. 13 (1). 13842. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-40804-3. PMC 10484975. PMID 37679444.

- ^ a b Sues, Hans-Dieter; Averianov, Alexander (2016). "Ornithomimidae (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Bissekty Formation (Upper Cretaceous: Turonian) of Uzbekistan". Cretaceous Research. 57: 90–110. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2015.07.012.

- ^ Choiniere, Jonah N.; Forster, Catherine A.; De Klerk, William J. (2012). "New information on Nqwebasaurus thwazi, a coelurosaurian theropod from the Early Cretaceous Kirkwood Formation in South Africa". Journal of African Earth Sciences. 71–72: 1–17. doi:10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2012.05.005.

- ^ a b c Cullen, Thomas M.; Zanno, Lindsay; Larson, Derek W.; Todd, Erinn; Currie, Philip J.; Evans, David C. (2021). "Anatomical, morphometric, and stratigraphic analyses of theropod biodiversity in the Upper Cretaceous (Campanian) Dinosaur Park Formation1". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 58 (9): 870–884. doi:10.1139/cjes-2020-0145.

- ^ a b c Fowler, Denver Warwick (2017-11-22). "Revised geochronology, correlation, and dinosaur stratigraphic ranges of the Santonian-Maastrichtian (Late Cretaceous) formations of the Western Interior of North America". PLOS ONE. 12 (11): e0188426. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0188426. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5699823. PMID 29166406.

- ^ Eberth, D.A. 2005. The geology. In: Currie, P.J., and Koppelhus, E.B. (eds), Dinosaur Provincial Park: A Spectacular Ancient Ecosystem Revealed. Indiana University Press: Bloomington and Indianapolis, p.54-82. ISBN 0-253-34595-2.

- ^ a b Alroy, John; Carrano, Matthew; Benson, Roger; Mannion, Philip (2021). "Qiupa, Luanchuan Basin (Cretaceous of China)". The Paleobiology Database.

- ^ Mallon, Jordan C.; Evans, David C.; Ryan, Michael J.; Anderson, Jason S. (2012). "Megaherbivorous dinosaur turnover in the Dinosaur Park Formation (Upper Campanian) of Alberta, Canada". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 350–352: 124–138. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2012.06.024.

- ^ Arbour, V. M.; Burns, M. E.; Sissons, R. L. (2009). "A redescription of the ankylosaurid dinosaur Dyoplosaurus acutosquameus Parks, 1924 (Ornithischia: Ankylosauria) and a revision of the genus". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (4): 1117–1135. doi:10.1671/039.029.0405. S2CID 85665879.

- ^ Lü, J. C.; Xu, L.; Chang, H. L.; Jia, S. H.; Zhang, J. M.; Gao, D. S.; Zhang, Y. Y.; Zhang, C. J.; Ding, F. (2018). "A new alvarezsaurid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous Qiupa Formation of Luanchuan, Henan Province, central China". China Geology. 1 (1): 28–35. Bibcode:2018CGeo....1...28L. doi:10.31035/cg2018005.

- ^ Lü, Junchang; Currie, Philip J.; Xu, Li; Zhang, Xingliao; Pu, Hanyong; Jia, Songhai (2013). "Chicken-sized oviraptorid dinosaurs from central China and their ontogenetic implications". Naturwissenschaften. 100 (2): 165–175. Bibcode:2013NW....100..165L. doi:10.1007/s00114-012-1007-0. PMID 23314810.

- ^ Xu, Li; Buffetaut, Eric; o'Connor, Jingmai; Zhang, Xingliao; Jia, Songhai; Zhang, Jiming; Chang, Huali; Tong, Haiyan (2021). "A new, remarkably preserved, enantiornithine bird from the Upper Cretaceous Qiupa Formation of Henan (Central China) and convergent evolution between enantiornithines and modern birds". Geological Magazine. 158 (11): 2087–2094. doi:10.1017/S0016756821000807.